Sep 22, 2025

What do TikTok videos and gold coins have in common? On the surface, not much. One is ephemeral social media content, often created and consumed in seconds; the other is a timeless store of value, painstakingly mined and universally prized. Yet the classroom of the future may blend these two worlds, treating student-created content as a form of Academic Capital – as valuable and rare as gold. In an age where social media posts and “likes” are the currency of fame, and quarterly reports drive business cycles, academic capital emerges as a new metric that could transform education. It borrows the viral energy of social platforms and the rigor of financial markets, and it just might upend our notions of academic success.

From Social Currency to Scholarly Capital

We’ve all heard of social capital. It used to be “who you know” and the elite accumulated social capital in boardrooms, with Rolodexes, and alumni clubs. But in the digital age it has gained cultural impact on platforms like Instagram or X (formerly Twitter). Post a witty tweet or a trendy dance video, and you collect reactions, follows, and fleeting attention. These posts are a dime a dozen. They’re the fiat currency of the internet age, churned out by the billions with little oversight.

Just as paper money can be printed in excess and lose value, content on social media is minted endlessly, vying for eyeballs in an overcrowded feed. Academic capital takes the opposite approach: it is deliberately scarce, earned through real effort, and meant to hold its value. In fact, students are limited to producing one major academic post per month under this model – a startlingly low “post rate” in the era of endless scrolling, but for good reason. Each piece of academic capital is like a gold coin: it must be mined through research and reflection, refined through multiple rounds of feedback, and validated for its quality. It’s a hard asset, not an easy “print.” Traditional school credits have become “soft” – too easily issued for short-term gains, leading colleges to distrust them. In contrast, Academic Capital requires quality academic work products and decentralized validation, functioning as “gold standard” credits backed by actual student work.

The analogy to money is more than metaphorical. In the 1970s, the U.S. dollar abandoned the gold standard and became “fiat” currency – valuable because we collectively believe in it, not because it’s tied to a precious metal. Similarly, today’s high school transcripts are rife with “fiat” credits, grades and credits that can be earned with minimal effort or inflated via lenient policies. Students often learn quickly that doing just enough to pass is the game of school: cram for a test, copy an assignment, behave well, and you collect the credit. Schools, under pressure to boost graduation rates, sometimes lower the bar – a dirty little secret where administrations quietly ease standards to produce better-looking stats. The result? Grade inflation and watered-down credits that colleges don’t know what to trust. Is it any wonder that universities have clung to SAT scores and AP exams as external validators? A transcript full of A’s might tell an admissions officer very little if those A’s were easily earned. In economic terms, printing too many dollars devalues the currency; printing too many unearned A’s does the same to the diploma.

Academic Capital flips this script. Each academic credit must be earned through a substantial piece of work – typically a polished audio or video presentation of about 10 minutes, akin to a mini documentary or podcast. Think of it as a student-produced TED Talk or investigative news segment. Crucially, this work is not just thrown online in raw form. It goes through multiple cycles of feedback and revision before it ever sees the light of day. A student might spend weeks or even an entire term researching a topic, drafting a script or essay, consulting peers and teachers for critique, and revising again and again. Only when the supervising teacher is satisfied that the work meets a rigorous standard – and that the student indeed put in the effort themselves – is it forwarded for external validation. In this model, the teacher acts as the first checkpoint, verifying authenticity and quality before an expert panel even sees it. Compare that to how things work on social media, where anyone can hit “post” in an instant, or even how things work with school tests, with speed essays and where an answer sheet holds simplistic, predetermined answers. Here, nothing is published without vetting and polish. I like to describe HS Cred as bringing “proof-of-work” to high school academics: students invest real sweat equity to mint each new credit.

This high bar means academic credits can no longer be cranked out assembly-line style. They’re hard to earn and thus have value because everyone knows the levels of review and rigor behind them. In fact, each published credit is backed by evidence: a digital portfolio. Imagine a college admissions officer scanning a QR code on a paper transcript and instantly watching the student’s capstone project for chemistry, or listening to their podcast on 19th-century French poetry. It sounds futuristic, but it’s exactly how the value of Academic Capital is built – transcripts that anyone can verify for themselves. No more hiding behind course titles and GPAs; let alone reductive metrics like 1285 on an SAT or 3 on the AP. The student’s actual work is on display. It’s a level of transparency reminiscent of the bitcoin ledger itself, where every coin is linked to a cryptographically verifiable transaction. Bitcoin showed that digital scarcity is possible in finance: by requiring proof-of-work and limiting supply, it created trust in a currency with no central authority. In the same way, Academic Capital aims to create trust in student achievements by making them scarce, earned, and open to inspection. What if, instead of a top-down, fiat system of soft credits, we could offer a decentralized system of gold standard credits which require published academic content? What if #PassionForLearning is kindled and grows stronger each year… led by the students, no less.

Students as Producers in an Upside-Down Classroom

In a flipped paradigm, Airbnb turned app users into a massive hotel chain. In the flipped classroom, students become content creators and storytellers. Here, high school reporters from the Jackson Youth Newsroom (Jackson, Mississippi) prepare to tell stories rooted in their community’s challenges and pride. Programs like this illustrate how culturally relevant, project-based work can ignite student engagement far beyond what any standardized test can achieve.

Stepping away from the economics metaphor, academic capital is about an inversion of classroom roles. For at least a century, education has been a top-down affair: the teacher delivers content, the students absorb and repeat it, and a standardized test at the end attempts to measure what stuck. It’s the educational analog of an assembly line. But what happens when you invert the power structure, making students the active drivers of learning? Remarkable things.

In the early days of the internet, skeptics doubted that user-generated content could ever amount to much – Stephen Weiswasser, a senior VP at ABC scoffed that “you aren’t going to turn passive consumers into active producers on the internet”, and that amateur creations would never find an audience or economic value. Those experts ate their words (one literally ate his printed column predicting the death of the internet). By the mid-2000s, blogs were being created at the rate of two per second, and today over 500 hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every minute. An entire creator economy blossomed, upending media and entertainment.

Now consider the traditional classroom – a place where, ironically, students often remain passive consumers (of lectures, textbooks, canned curricula). Academic Capital proposes that we treat students as creators and knowledge-makers, and let their work be the engine that drives learning. It’s a shift some have described as teachers serving as a “guide on the side” vs. the industrial model where they were the “sage on the stage.” Teachers aren’t less important in this model; they’re just not the solo source of knowledge. Instead, teachers become editors, coaches, and mentors, guiding students through the process of creation and inquiry.

This inversion taps into something powerful: student motivation. When you know your work isn’t just going to languish in a teacher’s drawer but will be published for a real audience, you naturally up your game. Educators have observed this phenomenon again and again. In my own school, students participated in public academic showcases (EXPOs) three times a year, presenting their research via short videos. The effect on morale was electric. Teachers and parents were stunned, even our school custodian commenting how he had “never seen students so motivated toward academic pursuits.”

The secret sauce? Authentic audience. Humans, teenagers very much included, care about how they appear in front of others. It is a trick I use when training adults: I ask workshop participants to discuss a topic in pairs, then I tell them they’ll have to record a summary of their discussion to be emailed with everyone in attendance. Instantly, the quality of the conversation shoots up – people focus, organize their thoughts, strive to sound insightful. This is the power of performance-based assessment, and it requires an authentic audience to witness the quality of work produced. In the digital age, sharing work is easier than ever, which means every classroom project can potentially find an audience beyond the classroom walls, given the right digital platform where this work can be published. Enter HS Cred.

Consider a traditional assignment: say, an essay on climate change. A student might do the bare minimum if only the teacher will read it. Now imagine the same student is told: “Turn this into a podcast episode or short video, and we’ll publish it online for the nation to hear.” Suddenly the task is imbued with purpose. It’s not just a grade; it’s a message. The student, now in the role of a young journalist or documentarian, must consider: How do I hook my audience? How do I back up my claims? Is my story compelling?

In educational jargon, this is called performance-based assessment – demonstrating skills and knowledge through a performance or product, rather than a bubble test. It’s not actually a new idea; it’s very old. Pedagogues know that performance-based assessment is an ancient form of assessment which incentivizes authentic learning. It is the gold standard of academic assessment. Long before Scantrons and AP exams, learning was often one-to-one and project-centric: think of apprentices crafting real objects or scholars debating orally to prove their mastery or native tribes passing wisdom across generations in rites of passage ceremonies and other rituals. Academic capital is, in a sense, a return to those roots – ancient practices refreshed for the digital era – combined with the massive distribution power of the internet. Students today are digital natives who see the world through the lens of creation and sharing. Rather than fighting for their attention with paperwork like worksheets, Academic Capital channels their creative energies into their school work. One might say it rebrands academic work as something exciting – something worth posting about.

Every Student a Storyteller (and Stakeholder)

Perhaps the best way to understand Academic Capital is to see it in action. Let’s take the example of The Bell, a nonprofit that trains high school students in New York City to become journalists. Over the past few years, more than 100 NYC students have gone through The Bell’s internships and collectively produced 120+ stories investigating issues in their schools. These aren’t puff pieces or token “student voice” projects – they are rigorous, reported stories that often highlight educational inequities. And they have real impact. For instance, Miseducation, The Bell’s flagship podcast, has aired student-produced episodes on topics ranging from segregated sports teams to controversial bathroom policies. In one recent episode, a sophomore at Stuyvesant High School dug into why financial literacy isn’t taught comprehensively in schools. “As a student reporter, I’ve seen firsthand how we’re set up to fail,” she wrote, noting that in New York – the financial capital of the world – personal finance is barely covered in the curriculum. She interviewed a teacher who started a finance course and an expert from a nonprofit, building a case that “every student deserves to be confident in their financial future.” The episode didn’t just earn her a good grade; it sparked listeners to sign petitions and contact legislators. Another student investigated queer activism in NYC schools, reclaiming the legacy of LGBTQ+ students who fought for their rights. Others have reported on why filling out the FAFSA feels dangerous for undocumented families, or how credit recovery programs might be failing the very kids they intend to help. These are complex, authentic issues drawn from the students’ own lives and communities. In tackling them, the students are interacting with the world as young journalists and young scientists, exactly as academic capital envisions.

It’s hard to overstate how transformative such experiences can be. One teen journalist described her internship as an “incredibly supportive environment where you not only speak about issues you care about but are taught to do so in a way that will be most engaging for the thousands of people who will hear you.” Another said she was “forever grateful for the one-of-a-kind experience…given a space to use the skills I’ve learned to produce something of such high quality.” These young people are owning their education – they are not just studying history, science, and language arts; they are applying those skills to create new knowledge and media. In economic terms, they’ve become investors. But instead of investing money, they’re investing time, talent, and creativity. The return on investment is twofold: first, a tangible piece of content (an article, a podcast, a research presentation) that becomes part of their personal portfolio; and second, the social and academic capital that comes with having created something meaningful. Classmates might see them as leaders. Teachers treat them as capable of professional-caliber work. Colleges and employers take note – a portfolio of high-quality work can shine brighter than a transcript full of perfect test scores. After all, which tells a college more about a student: knowing they got an A in English, or hearing the podcast episode they wrote and produced about local environmental policy?

From the academic capital perspective, students are the ultimate stakeholders in education. They are, as the HS Cred whitepaper puts it, the “investor class” of this new form of capital – and their currency is human attention. They pour in their attention and effort, and in return they create attention from others in the form of an audience who cares about their work. It’s a virtuous cycle of attention: students invest attention to create great work, great work garners attention from viewers/listeners, and that recognition, in turn, motivates students further. Notice how different this is from the typical high school incentive structure. In too many schools, students are just consumers of content, and their main incentive is to avoid negative consequences: don’t fail, don’t get grounded for a bad report card, etc. Academic capital introduces incentives more akin to the real world of creative work or entrepreneurship. Publish something awesome, and you get rewarded – not with a gold star, but with actual viewers, impact, and a credential that is substantive. It eliminates noise in educational data because the focus is solely on the quality of work, not on ancillary factors like attendance or behavior points. In other words, it makes the signal (the student’s capability and drive) much clearer. The very concept of failure literally disappears since work that is not published because of poor quality is simply absent. You either earn units of academic capital or you don’t, there’s no such thing as a “D” or an “F” on your transcript, there’s just the count of how many pieces were approved for publication. Educators call this “strenghts-based” incentives. We focus and celebrate student achievement. That’s the only incentive. All carrot, no stick. Pure nutritional value for the mind. In a world where talent is equally distributed but opportunity is not, academic capital offers much needed opportunity without limits. It is then up to students to run with it.

Data is destiny. So change the data.

Here’s the quiet truth about schools: data drives behavior the way profits drive companies. Grades, test scores, graduation rates—these are education’s quarterly earnings. They shape policy, funding, rankings, staffing, scholarships, interventions. If the data rewards coverage and compliance, we will teach to coverage and compliance.

Academic capital changes the data. It swaps low-resolution compliance metrics for high-resolution learning metrics. The “currency of the realm” becomes student work that shows thinking, not point totals. When districts and states aggregate that kind of data—validated performance across writing, analysis, inquiry, oral defense—the incentives cascade:

Teachers have air cover to coach projects instead of cram for tests.

Students discover that attention + revision = value, and they act accordingly.

Schools reorganize around studios, showcases, and expert review.

Funders and policymakers can finally see where deep learning is happening—and support it.

Change the metric and you change the motive. In a system as vast as American education, a better measure is the highest-leverage lever we have.

Back to the Future of Learning

If all of this sounds a bit idealistic – well, it is. Transforming the entrenched systems of schooling is a daunting task. But the movement toward performance-based, student-driven learning is gaining traction. Even at policy levels, there’s recognition that our century-old reliance on multiple-choice tests and cookie-cutter curricula isn’t cutting it. In recent years, states like Kentucky, Virginia, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New York have begun experimenting with alternatives to standardized exams, allowing students to “show mastery through performance-based assessments” and portfolios. 2,085 U.S. colleges have gone test-optional, sending a signal that they’re looking for new ways to identify talent. The timing is ripe for a concept like academic capital to take root. Technology, too, is on its side: we now have the tools – from ubiquitous video cameras to secure blockchain ledgers – to implement a system of decentralized, verifiable academic credits at scale. HS Credit is already beta-testing this approach, allowing any 11th or 12th grader to upload a polished 10-minute podcast or video, have it evaluated by three expert educators (plus their own teacher) according to a rigorous rubric, and “mint” it as an official credit on a digital transcript. There’s even blockchain involved in the design: each credit, once earned, will become a non-fungible token (an “ntNFT” – non-transferable NFT) owned by the student, ensuring that their achievement can’t be altered or taken away and will live on even if the original platform disappears. The use of Web3 buzzwords aside, the essence is that the student owns their achievement in a very real sense.

It’s telling that as an early adopter of this model, I invoke ancient wisdom alongside cutting-edge tech. I point to tribal oral traditions and apprenticeship models in the same breath as blockchains and AI. In a way, academic capital is about humanizing education through technology. It’s using 21st-century tools (high-speed internet, digital media, cryptographic records) to facilitate what is fundamentally a very human, very personal process: a young person learning about the world, expressing themselves, and being heard. This process respects cultural relevance and individual context. A student in Mississippi might explore the history of local civil rights activism; a student in New York City might examine the impact of gentrification on their neighborhood schools. Each can pursue topics that ignite their curiosity or speak to their lived experience, rather than marching through a generic syllabus. The diversity of content becomes a strength: the shared platform can host everything from a science experiment in a rural farming community to a journalistic exposé in an urban district. And far from these being isolated projects, they accumulate into a body of youth-created knowledge – a ledger of academic accounts that society can tap into. So let’s listen to the youth and hear their stories of transformation, of academic exploration, and of experiences they are having in this age of rapid change. They are the generation that has never known life without the internet; they will lead us deeper into the digital era. Shouldn’t we equip them to not just navigate that era, but to shape it?

In the end, academic capital isn’t about diminishing social media or financial capital – it’s about adding a new kind of value to the world. Imagine a future where millions of students regularly publish scholarly content: analyses, narratives, innovations, art. Not junk posts or copied Wikipedia text, but original work that has been honed and vetted. The collective output would be astonishing – a vast, global library of student-led media showcasing how the next generation views our world. We’d gain insight from fresh eyes: youth from different cultures and backgrounds investigating problems and proposing solutions. It’s often said that today’s students will have to solve tomorrow’s problems, from climate change to social injustice. Perhaps we should let them start solving — and credit them for it — right now. That, in essence, is academic capital: recognizing and rewarding the real intellectual labor of students in a way that both builds their personal “wealth” of skills and knowledge and contributes to our shared societal wealth of ideas.

The old educational regime treated students as products of a system, outputs to be measured. The new paradigm treats students as producers and stakeholders, with a claim of ownership in their learning. It’s a profound shift – one that might feel as jarring as going from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles and space shuttles. But as we’ve learned in industry, disruption can be deeply generative. The digital inversion of music, journalism, retail, and other fields didn’t destroy those fields; it liberated and expanded them (albeit not without pains). Likewise, flipping the script so that academic credit must be earned by creating something real could liberate untold potential in our schools. It sets a higher bar, but also a more meaningful one. And when students clear that bar, the accomplishment is theirs. They carry it forward as part of their identity. As one student proudly declared after completing a project, “I used the skills I’ve learned to produce something of such high quality.” That pride, that sense of capability and ownership, is worth more than its weight in gold.

In the coming years, as this idea gains momentum, parents, educators, and students themselves will face a choice: continue with business-as-usual, or dare to redefine success in education. Academic capital offers a compelling vision of the latter – one where high school isn’t just about accumulating grades, but about building a portfolio of intellectual accomplishments. It feels more like launching a career than finishing a checklist. It treats a 17-year-old’s well-researched podcast on city budget cuts with the respect we usually reserve for a professional report – and in doing so, it shows the student that their voice matters. It’s engaging, it’s fun, it’s challenging, and yes, it’s a bit radical. But if you ask the students who’ve gotten a taste of it, you’ll find that nothing reinvigorates the love of learning quite like being trusted to hold the pen, the camera, or the microphone. This is academic capital: learning by creating, knowledge by doing, and success measured in the currency of ideas and understanding – a currency that, unlike a test score, just might hold its value for a lifetime.

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

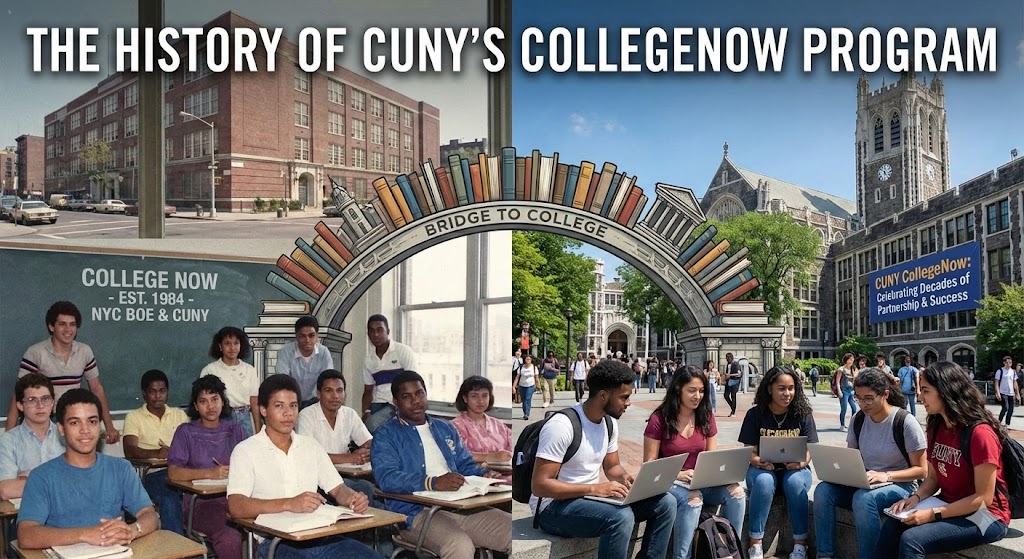

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025