Sep 29, 2025

Summary: With 2,085+ four‑year colleges now test‑optional or test‑free for fall 2025 (up from “1,900+” just two cycles ago), the United States has effectively ended the SAT/ACT era as a universal gatekeeper. That shift opened doors—but it also created an assessment vacuum. Admissions offices, buffeted by record application volumes, grade inflation, FAFSA shocks, AI‑assisted essays, and new legal constraints post‑SFFA, are grasping for valid, equitable, actionable evidence of college readiness. It’s time to move past the false binary of “tests or no tests” and toward a performance‑based readiness signal—a portable, verified record of what students can actually do. Think of it as building students’ academic capital: rigorously‑scored demonstrations of inquiry, analysis, problem‑solving, and communication that travel with them into college and beyond.

How we got here

Years before higher ed shifted policy, the K–12 opt‑out movement signaled broad public skepticism about high‑stakes standardized testing. In New York, for example, roughly 20% of grades 3–8 students refused the state’s Common Core exams in 2015—a headline‑grabbing peak that reverberated nationally. While opt‑out targeted elementary and middle‑school accountability tests (not college admissions), it helped normalize critical questioning of what these tests measure and whom they advantage, setting the stage for later changes in admissions.

Then COVID‑19 turned skepticism into action. Test centers closed and SAT/ACT administrations were canceled in spring 2020, prompting hundreds of colleges to adopt emergency test‑optional policies. Public systems led the way: the University of California suspended SAT/ACT (moving to test‑blind for 2023–24), and the California State University first suspended scores for 2021–22 before eliminating them entirely in 2022. By fall 2022, more than 1,800 four‑year campuses—nearly 80%—were test‑optional or test‑free, cementing a national pivot that has persisted beyond the pandemic’s peak.

Together, grassroots pushback and pandemic disruptions moved the center of gravity in college admissions from single‑sitting tests toward broader evidence of readiness. As of this year, nearly 2,100 accredited, bachelor‑granting institutions advertise ACT/SAT‑optional or test‑free policies for applicants seeking to enroll in 2025 and beyond—an unmistakable rebalancing of U.S. admissions away from high‑stakes, one‑shot exams.

The shift toward test‑optional has solid backing in research and practice. A multi‑campus NACAC study found that dropping score requirements typically increased applications and raised representation of underrepresented students in both applicant pools and entering classes. The effect on low‑income enrollment (measured by Pell Grant eligibility) was uneven—some colleges enrolled more Pell‑eligible students, while others saw little or no change. Importantly, students who chose not to submit scores graduated at rates similar to those who did. In short, test‑optional policies often achieved their access goals. Later scholarly reviews—for example, by Rebecca Zwick—show that results vary by institution, but the overall pattern remains consistent.

There is also the issue of what test scores actually capture. Large‑sample analyses show that SAT/ACT scores are much more tightly linked to family income than school‑specific measures like GPA. Using nationally representative data, the Penn Wharton Budget Model reports that SAT math and ACT scores correlate about 0.22 with household income, roughly three times the income‑link seen for high‑school GPA or class rank—and concludes that selecting on such measures “will bias more towards wealthier students than selection solely on school‑specific measures.” In California’s UC system, family background (income, parental education, race/ethnicity) explains more than 40% of the variance in SAT/ACT scores among applicants, compared with <10% of the variance in high‑school grades. At the same time, Opportunity Insights shows that low‑ and middle‑income students attend selective colleges at far lower rates than peers with the same test scores, highlighting pipeline barriers that operate even when academic indicators are held constant.

Because SAT/ACT scores are far more correlated with household income than GPAs, relying on tests as primary signals risks sorting by class more than surfacing potential. I saw this first hand as a high school principal the extent to which academic potential is evenly distributed across socioeconomic indicators while opportunity is decidedly not.

The vacuum test‑optional created

Going test‑optional did not make selection easier; it redistributed weight onto other signals—chiefly GPA, course rigor (e.g. AP courses), recommendations, activities, and essays. That has practical consequences:

Continued advantage based on income. Students from affluent homes have greater access to advanced courses, opportunities for meaningful extra-curricular activities, staff that can provide reliable recommendations and coaching support in college essay production.

GPA inflation and inconsistency. Over the last decade, average high‑school GPAs climbed while ACT scores slid, widening the gap between local grading signals and externally normed benchmarks—complicating cross‑school comparisons, especially in large public systems.

Bigger, noisier pools. Common App’s end‑of‑season 2025 analysis shows applicants and applications up again, with test reporters rising for the first time since 2021–22—a signal that families sense scores matter at some institutions, even when “optional.” The result: more complex reading and modeling work for admissions offices.

AI‑era essays. Post‑GPT, authenticity checks on personal statements consume staff time and rarely yield stable, comparable indicators of readiness. (Even selective colleges that reinstated testing say the point is predictive utility, not nostalgia.)

Under legal scrutiny after Students for Fair Admissions, institutions are also re‑auditing selection factors to avoid practices that could function as prohibited proxies for race—compounding uncertainty about what evidence can be used, how, and to what end. Federal guidance since August 2023 clarifies what remains lawful and urges careful policy evaluation.

Do tests predict success? Yes—and no. Context matters.

This debate often gets framed as a referendum on a single variable. Reality is more nuanced:

At some campuses (e.g., UT Austin), internal analyses found that standardized scores, combined with GPA and rank, improved early risk identification and major placement; UT reinstated a requirement beginning with fall 2025 on those predictive grounds.

Across the large University of California datasets, high‑school GPA has been the stronger predictor of longer‑term outcomes (cumulative GPA, graduation) than SAT/ACT, with tests adding little unique variance once richer high‑school information is modeled.

Syntheses of multiple test‑optional implementations show mixed effects on diversity and performance, depending on selectivity, aid, recruitment, and academic support investments. Translation: the system you build around any metric matters more than the metric alone.

Meanwhile, a handful of outliers are experimenting in the other direction. The University of Austin (UATX), for example, introduced a “merit‑first” policy with automatic admission above specific SAT/ACT/CLT thresholds and a streamlined review below them—an illustration of how polarized the policy environment has become. But these remain edge cases, not the trendline.

Is there a better alternative to standardized tests?

A growing body of research points to a third path: performance‑based assessment. Rather than inferring readiness from time‑limited items or local grades alone, colleges can examine calibrated, cross‑school evidence of what students can actually do: sustained research, data analysis, scientific investigations, argumentative writing with sources, oral defense, and problem solving on real‑world tasks.

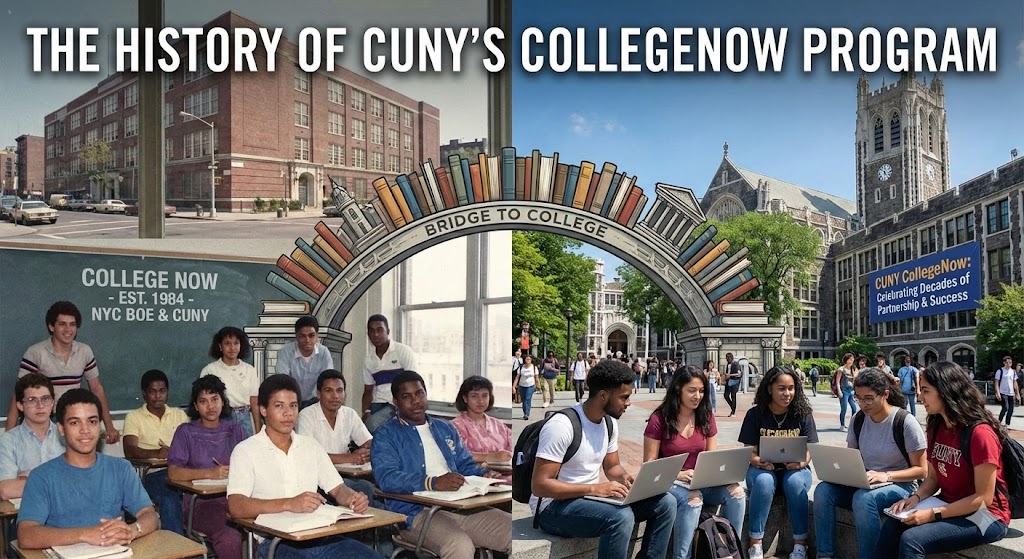

This isn’t hypothetical. The Learning Policy Institute’s study of the CUNY–New York Performance Standards Consortium pilot found that students admitted with portfolios of high‑quality performance tasks—despite lower SATs—tended to earn higher first‑semester GPAs, accumulate more credits, and persist at higher rates than peers from other NYC schools. LPI’s earlier synthesis similarly documented how well‑designed performance systems (in U.S. networks and internationally) can serve both learning and admissions.

The Consortium’s model is especially instructive: students complete practitioner‑designed, externally reviewed PBATs (e.g., literary analysis, social science research, original experiments with oral defenses). The system includes common rubrics, moderation, and quality assurance—the very features admissions needs to trust performance at scale.

Professional organizations have been moving this direction as well. The NEA’s Principles for the Future of Assessment call for systems that center student learning, use multiple measures, and reduce high‑stakes distortions—conditions that performance assessment is built to meet.

And the policy wind is shifting. New York’s Board of Regents formally adopted a statewide Portrait of a Graduate framework in July 2025 and sketched a timeline to phase out Regents exams as graduation requirements beginning in 2027–28, opening the door to capstones, internships, and other demonstrations of mastery. That change will push millions of performance artifacts into the K–12 pipeline—if higher ed can recognize, validate, and use them.

From evidence to Academic Capital

Today, admissions is starved for reliable indicators and flooded with raw content. The solution is not to lurch back to a single test score, nor to pretend grades and essays alone can carry the predictive load. What colleges actually need is a portfolio of standardized, performance‑based signals—a bank of academic capital that travels across high schools, regions, and contexts:

Core competencies, not just courses. Evidence aligned to broadly accepted constructs—analytic writing with sources, quantitative reasoning & modeling, scientific inquiry, civic or community problem‑solving, and oral communication.

Calibrated scoring. Common rubrics, scorer training, moderation, and external audits—borrowing methods from the New York Consortium and other validated systems—are essential to comparability.

Verifiability and integrity. Secure provenance (timestamps, teacher attestations, plagiarism/AI‑assist checks) and cross‑checks (e.g., oral defenses or live tasks) to mitigate ghostwriting and AI inflation.

Actionable analytics. For institutional research, performance indicators can sit alongside GPA, course history, and (where available) test scores in models predicting first‑term success, credit momentum, and risk—much as UT Austin illustrated with its data‑informed approach.

Legal defensibility. Rubrics must evaluate work and skills, not identity or proxies for identity—consistent with post‑SFFA federal guidance.

In short: Academic Capital is the currency that lets colleges read beyond numbers without falling into subjectivity. It is the bridge between K–12’s emergent performance systems and higher ed’s need for valid, scalable signals. That is exactly why I created the HS Cred platform.

What admissions offices can do

Name the vacuum. Publish a plain‑language account of what matters in your review and why—especially how you read GPA amidst inflation and how you weigh (or ignore) scores in a test‑optional context. Families respond to transparency; your modeling will be more stable when applicants submit the evidence you actually use.

Pilot a “three‑artifact” requirement for all applicants (or specific cohorts): one analytic writing sample with sources, one quantitative or scientific investigation, and one oral defense or public presentation. Allow artifacts from accredited course‑embedded tasks, capstones, CTE/community projects, or state‑approved graduation exhibitions.

Adopt common rubrics and moderation. Start with open rubrics such as those aligned to LPI/Consortium exemplars; contract for scorer training and periodic double‑scoring. This is how you turn diverse work products into comparable evidence.

Integrate Academic Capital into predictive models. Score bands from performance tasks often map cleanly to first‑term GPA and credit completion—outcomes your student success teams already track. Use those relationships to inform advising and early supports, just as campuses have used testing, GPA, and rank.

Build K–12 ↔ higher‑ed pipelines. In states adopting Portraits of a Graduate (e.g., New York), co‑design capstones and rubrics with district partners so artifacts arrive in a format your readers can rapidly interpret.

Stress‑test legal and equity safeguards. Document how your performance‑based criteria align to program demands, how scorers are trained for bias mitigation, and how artifacts are verified—so your policy is both fair and defensible.

Or launch an HS Cred pilot program, which does all of this for you.

We’ve tried one‑dimensional selection (test scores). We’ve tried kaleidoscopic “holistic” reading, often anchored by locally variable grades. Neither alone solves today’s challenges. A performance‑based, research‑grounded framework lets us keep the access gains of test‑optional, preserve the predictive value institutions find in structured evidence, and reduce dependence on signals most correlated with wealth.

The research base is already here:

Test‑optional can expand opportunity without harming completion.

High‑school task performance is a sturdier long‑run predictor than one‑off exams.

Calibrated performance tasks predict success and narrow gaps when students are taught and assessed through deeper learning.

And the policy tide is moving that way—away from one‑size‑fits‑all tests and toward graduate portraits that demand authentic demonstrations. The opportunity now is for higher education to meet K–12 halfway: to recognize, score, and reward the academic capital students are building.

If the SAT/ACT era defined the last generation of admissions, the next one will be defined by what students can show they can do. That’s the future worth building—fairer for students, more usable for colleges, and truer to our mission as educators.

HS Cred is a platform designed for colleges and universities to make this transition effortlessly. The key is that we pay content specialists to do the portfolio grading rather than expecting admissions officers to do it. The result is high meaningful data at the fingertips of participating admissions offices.

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025