Jan 26, 2026

The theme of Big Picture Learning's Leadership Summit this week is "the city as the classroom." It's a powerful, essential idea—that a community can teach what no curriculum can. But as we celebrate the power of place, my mind keeps drifting beyond the city limits. The city is our teacher. But the world must be our audience.

What happens when a student's best work doesn't stay where it was made? When a research project born in Harlem can be watched in Osaka? When a science presentation created in a rural Kentucky classroom catches the eye of a professor in California? This isn't a future problem; it's a present possibility. We are in a digital era where student work must travel.

Anyone who has witnessed a BPL exhibition knows the power of watching a young person synthesize months of inquiry, internship experience, and personal growth into a coherent narrative of intellectual achievement. The student stands before people who know them well, people who have watched their journey, and demonstrates what they've learned by showing what they can do. It is assessment at its finest. It is everything standardized testing is not.

I've seen this pattern repeat for decades. A student spends months investigating environmental racism in her neighborhood, synthesizes primary sources, interviews community members, writes a paper that would hold its own in any undergraduate seminar. And then it's over. The exhibition ends. The audience disperses. When that student eventually applies to college, what travels with her? A transcript listing course names and grades. Perhaps a letter from her advisor. Maybe an essay that an admissions officer will skim in two minutes, wondering whether AI wrote it. The exhibition itself—the actual evidence of thinking—stays behind. The brilliant work becomes a fleeting memory rather than an indelible credential. This is the tragedy we are working to end.

This problem is not uniquely American. Six thousand miles away, Japanese educators face an eerily parallel challenge. Tankyu—Japan's inquiry-based learning movement—has transformed how students engage with complex questions in high schools across the country. Students investigate problems that matter to their communities, develop original research, and present their findings to panels of teachers and peers. The pedagogical philosophy mirrors BPL's in striking ways: student agency, authentic questions, real-world application, public defense of learning. And yet Tankyu faces the same infrastructure gap. When those students apply to universities, the inquiry work that defined their high school experience becomes invisible. Admissions committees see test scores and grades. They don't see the student think.

The stakes in Japan may be even higher. Tankyu exists in tension with a testing culture that remains deeply entrenched. Without pathways to make inquiry-based work legible to universities, the movement risks being squeezed out—dismissed as enrichment rather than recognized as rigorous academic preparation. Educators who have devoted years to building Tankyu programs watch their students' best work disappear into digital filing cabinets while entrance exams determine futures.

This is the gap that haunts me on both sides of the Pacific. BPL schools and Tankyu programs have spent decades perfecting authentic assessment. Their students produce work that would hold its own in any undergraduate seminar. At schools like The Met in Providence or Gibson Ek in Washington or Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School in the Bronx—and at forward-thinking high schools in Osaka and Kyoto and Tokyo—young people investigate questions that matter to them, work alongside professionals in real organizations, and present their findings to panels that hold them to genuine criteria. This is exactly what educational research says we should be doing. This is exactly what Portrait of a Graduate frameworks are trying to scale across New York State. The hard pedagogical work has already been done.

Imagine what portable really means. For over a century, portability in education meant a standardized exam score—a number that colleges could use as a common yardstick regardless of where you went to school. That number was crude, but it traveled. Now we're talking about something far richer: portfolios that travel. A video presentation created in one city and approved for publication on HS Cred can be watched in another country the next day. A research paper uploaded as a video presentation can be reviewed alongside applications from students on different continents. These student-created artifacts aren't just crossing city lines. They're crossing language barriers and time zones. Some of our recent student videos already carry subtitles in other languages—a quiet testament to how far compelling student work can go.

The key word is compelling. Opening student work to the world only matters if that work is credible. This is where the design becomes critical. HS Cred is not a free-for-all upload site. Each project that travels beyond the school has passed through checkpoints before being published. The student's own teacher vets the work through multiple rounds of feedback and revision. Only when the supervising teacher confirms the work is authentic and rigorous does it move forward for independent validation by an academic institution. Then three subject-matter experts—university-selected experts with no connection to the student—review the submission blindly, judging only the work itself against a public rubric. This multi-layer publication process ensures that when a student's work travels, it carries weight. It's not just a claim of quality. It's evidence.

The result is something new in education: a credential that shows rather than tells. When an admissions officer clicks a link on an HS Cred transcript, they don't see a letter grade or a test score. They see the student's actual presentation. They watch the student explain their methodology, defend their conclusions, respond to complexity. Either the student can think, or they cannot. Either they understand their material deeply enough to explain it, or they do not. There is no hiding behind manufactured polish. The work speaks for itself.

This matters enormously for equity. Traditional metrics have always favored students from well-resourced schools. An A from a prestigious prep school carries more weight than an A from an under-resourced public high school, even if the second student worked harder and learned more. Standardized tests correlate more tightly with family income than with future college success. But when the work itself is visible, the playing field shifts. A multilingual student who struggles on an English-heavy exam might produce a research project that demonstrates genuine analytical skill. A student from a school without AP courses can still demonstrate advanced knowledge by independently delving into a topic and presenting it. Background recedes. What remains is evidence of thinking. This holds true whether we're talking about a first-generation college student in the Bronx or an inquiry-driven learner in a Japanese prefecture far from Tokyo's elite institutions. Wealthy students can pay to have expert video editing, but they cannot compete with the inspiration that is so clear when a student is truly hungry to learn despite substantial barriers they have to overcome. These barriers become an advantage in and of themselves that cannot be faked by an expensive tutor.

For BPL students, this conversion is natural. They already know how to investigate questions that matter. They already know how to present findings to demanding audiences. They already know how to defend their conclusions under questioning. Converting an exhibition into a ten-minute video isn't learning a new skill—it's capturing work they've already done in a format that travels. The same is true for Tankyu students. The inquiry methodology already produces presentation-ready work. What's been missing is the channel to carry it beyond school walls.

I keep returning to one image: a student completing their senior exhibition or their culminating Tankyu presentation. They've spent months on an internship or an original research project, prepared a presentation that synthesizes everything they've learned about a field they care about. They stand before their advisory or their inquiry panel and deliver the performance of their young academic life. It's brilliant. It's moving. It demonstrates exactly the capabilities that colleges claim to value. And then that student applies to universities, and none of those admissions officers see what happened. They see numbers. They see letters. They don't see the student thinking on their feet.

Now imagine the same presentation, recorded and uploaded. The student's advisor attests to its authenticity. Three independent faculty members evaluate it against public criteria. The work is approved and published. When that student applies to college, they include a link. The admissions officer clicks it. They watch. They see what the student can actually do. And because the platform is global, a student in Osaka can have their work evaluated by a professor in New York while a student in Providence can be validated in Tokyo. The very choice of which channel to have review and potentially publish their work tells us volumes about the student making this choice.

The educators gathering this week in New York already understand this. They've built schools around the conviction that students learn by doing, that assessment should capture authentic capability, that relationships and real-world engagement produce outcomes traditional schooling cannot match. The research validates what they've known for decades: students from BPL schools persist in college at higher rates, achieve higher GPAs, and demonstrate the self-directed learning skills that predict success in complex environments.

Tankyu educators in Japan understand this too. They've been fighting the same fight, often against steeper odds. They know their students produce remarkable work. They know that work demonstrates capabilities no standardized test can capture. They've been waiting for someone to build the bridge that connects their innovations to the wider world.

The question now is infrastructure. How do we ensure that the excellent work happening in BPL schools and Tankyu programs—and in the growing number of schools adopting similar approaches worldwide—becomes visible to the institutions making decisions about students' futures? How do we build systems that reward authentic assessment rather than penalizing schools for innovating beyond standardized metrics?

The city as teacher, the world as audience. This is the invitation. BPL schools have already done the hard pedagogical work. Tankyu educators have already done the hard pedagogical work. They've proven that exhibitions and inquiry presentations reveal student capability better than any bubble sheet. They've demonstrated that young people rise to meet genuine challenges when adults believe in them and hold them accountable. What remains is to build the channels that let that work travel—to ensure that when a student produces something excellent in one place, it can be seen and validated and recognized anywhere.

The summit theme asks us to see the city as a classroom. I'm asking us to see the world as an audience. The students are ready. The work is ready. The infrastructure exists. What remains is for institutions everywhere—universities in New York and Tokyo, scholarship committees in California and Kyoto, employers who value thinking over credentials—to say yes. Yes to student work that arrives not as a test score or a grade point average, but as unassailable evidence of thinking.

Let the work speak. It's time we begin to listen.

Nadav Zeimer is the founder of HS Cred, Inc. and a former NYC turnaround principal. The Big Picture Learning Leadership Summit takes place January 26–29, 2026 in New York City. For Japanese readers interested in connecting Tankyu work to global audiences, visit hscredjp.org.

#PassionForLearning #AcademicCapital #BPLLeadershipSummit #探究学習

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

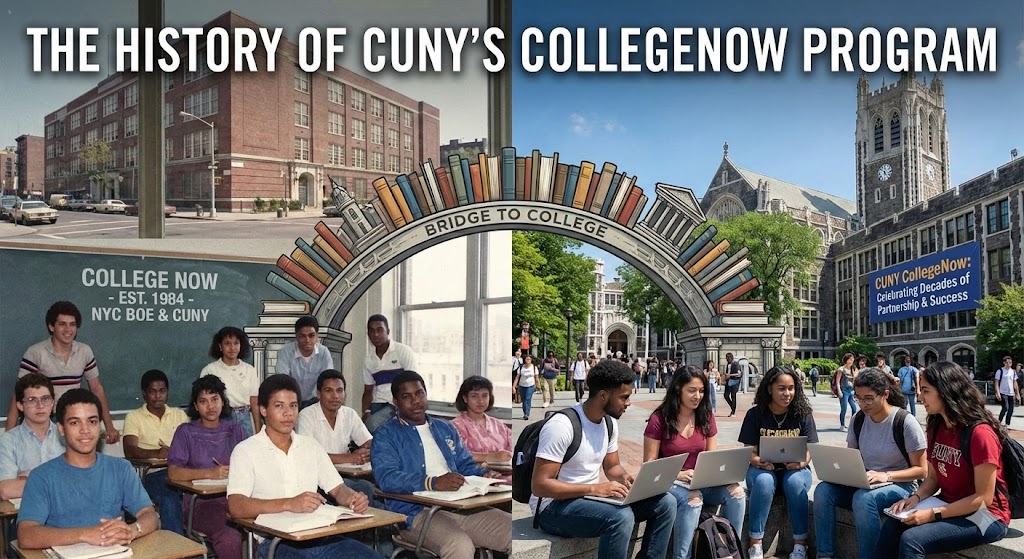

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025