Nov 18, 2025

As New York State phases out Regents exams by 2028 and implements its Portrait of a Graduate (POG) framework, policymakers face a choice that will shape the future of assessment for a generation of students. This choice is not about whether to reform assessment—that decision has already been made. Rather, it is about how we reform it, and the path we choose will determine whether we truly transform learning or simply replace one bureaucratic system with another.

The critical question is: Should the Portrait of a Graduate be implemented in school buildings through high-inference competency-based assessment (CBA), which focuses on tracking dozens of discrete skills, or low-inference performance-based assessment (PBA), which focuses on validating substantial student-created work?

While these approaches share a reformist goal, the distinction between them reveals fundamentally different visions for student learning, teacher autonomy, and educational equity. At its heart, CBA is a high-inference approach, asking educators to make complex judgments about a student's internal, overall capability. PBA is a low-inference approach, focusing only on the objective quality of a piece of work.

To understand what is at stake, we must first acknowledge what we are moving away from: traditional grading. With its mix of multiple-choice scores, participation points, and homework completion averaged into a single letter grade, the old system prioritized "seat time" over demonstrable learning. This point-game approach allowed students to pass without genuine skill competency, rewarding them for learning the system of point accumulation rather than learning to do difficult things.

The Leap of Inference

To be clear, competency-based assessment isn't wrong—it's overcomplicated. At the school level, a well-designed CBA system beats traditional grading every time. The problem emerges at scale: when we ask every district to build its own competency framework, we multiply bureaucracy without multiplying clarity.

Under CBA, educators identify specific academic skills—"competencies"—and evaluate students’ "mastery" based on evidence that students can consistently demonstrate proficiency. This focus on skills allows for targeted support and replaces the permanent stigma of failure with a "not yet" mindset. Schools that adopt common competency frameworks serve students far better than traditional grading systems.

The downside, however, is that CBA is structurally overcomplicated and high-inference. CBA attempts to offer a holistic assessment of the learner but does so by imposing a restricted, top-down list of chosen academic skills. Students are rewarded for demonstrating mastery of only those specific competencies. Skills not on the list go unmeasured, and any learner who does not naturally fit the "portrait" designed by administrators is at a disadvantage. This requires a tremendous amount of overhead in teacher paperwork and administrative mandates—time that is taken directly away from supporting students.

The concept of "mastery" is central to CBA implementation, suggesting arrival at a destination rather than an expectation of lifelong learning. More critically, CBA requires educators to evaluate not just a piece of student work, but to then extrapolate and make an inferred judgment about the abilities of the human learner. This is a massive, high-inference leap that adds inadvertent bias, clouding the academic assessment. A competency framework is little more than a distorted lens through which these inferences are to be made.

The Bottom-Up Path

Performance-Based Assessment (PBA) achieves the same goal—project-based, student-centered learning—with significantly less systemic complexity. Performance-based assessment focuses on evaluating individual artifacts of student work using a rigorous rubric. This is the low-inference approach: the evidence is contained entirely within the work product itself.

Think of it this way: CBA is built using PBA as its foundation. PBA is 'Layer 1,' used to evaluate student work, each piece standing on its own. CBA then attempts to form a 'Layer 2' by extrapolating a judgment about the learner from the PBA evidence.

Crucially, PBA demands a laser-like focus on project-based learning. By definition, you cannot do performance-based assessment without engaging students in meaningful, substantial work products. The assessment method itself demands the pedagogical practice we seek. With CBA you are free to continue using standardized exams and worksheets as evidence of skill development alongside PBA assessments.

PBA-focused practice removes the entire bureaucratic "Layer 2" from the school workload, thus reducing paperwork for educators. High schools focused on PBA leave the work of aggregation, inference, and overall learner judgment to state officials, universities, and others outside their walls. Educators focus their efforts on guiding students to a portfolio of quality academic work exemplars, thereby maximizing their time in the classroom.

PBA asks simply: can the student produce high-quality academic work in a variety of subject areas? This approach allows work products to be individually complex, showcasing a myriad of skills interacting organically to produce a solid product—which is much more like the world of work and college.

Clarity for College Admissions

Why should high schools involve themselves in a complex, high-inference process that ultimately muddies the view college admissions officers get of the student?

A college receives a clear, pure Performance-Based Assessment (PBA) transcript from a platform like HSCred, where they can directly review the student's work and the related rubric. This allows the college to make its own assessment about the student as a whole. HSCred, for instance, includes multiple independent evaluators outside of the school, further lessening the assessment burden on individual teachers.

In contrast, a Competency-Based Assessment (CBA) platform like mastery.org requires educators to collect student work as "evidence of mastery" against a school-defined competency framework. The problem is that these complex CBA frameworks are unique to every high school, forcing college admissions officers to navigate numerous opaque, high-inference narratives just to find the low-inference data—the student's performance—they need.

PBA keeps things simple by providing the "proof-of-work." The admissions team gets 20 independently validated student achievements so that they can do the work of CBA (the evaluation of the learner as a scholar) within the context of their own competency framework. The individual scholar chooses how to present themselves, allowing the university to define its own vision of the ideal candidate.

Getting Implementation Right: Focus on Student Work

POG defines competencies that represent the "portrait" of what graduates should be able to do. The danger is that this state-level framework, while well-intentioned, could be implemented as a statewide CBA initiative—essentially, a new generation of Common Core Learning Standards for all students, implemented through competency tracking. Yes, POG itself defines a portrait—but the question is who holds the brush. Under CBA, administrators paint the portrait through competency checklists. Under PBA, students assemble their own portrait through a body of work that meets common standards while remaining uniquely theirs.

POG emerges from the Performance Standards Consortium, which pioneered PBA as an alternative to Regents exams. The Consortium model succeeds precisely because it focuses on authentic student work. In fact, on the New York State official POG website, Performance-Based Assessment is mentioned, while the term Competency-Based Assessment is absent.

Individual districts will decide which path to take. Do they focus on high-quality validation of student work products presented to authentic audiences? Or do they spend their time articulating and evaluating locally-defined subskill lists?

The Common Core offered a cautionary tale: well-intentioned standards, rigidly implemented and tied to high-stakes accountability, can narrow curriculum. A competency-based POG risks similar pitfalls—new mandates that, despite emphasizing skills, still impose a uniform vision on all students and schools through administrative tracking.

A Truly Performance-Based Policy

Truly performance-based implementation would establish common rubrics and PBATs (Performance-Based Assessment Tasks) for students to work within, ensuring each content area is represented.

Focus on Work: Develop robust rubrics that multiple assessors are trained to apply reliably, focusing on the work itself rather than tracking progress through narrow competency hierarchies.

Empower Teachers: Leave teachers the space to focus on one high-quality project at a time. PBA keeps focus where it belongs: on classrooms where students engage in meaningful project-based learning. CBA tends toward administrative tracking systems.

Decentralize Inference: Leave it to students, state officials, and university admissions officers to make inferences about individual learners from the portfolio of evidence.

The Performance Standards Consortium proves this model works. Their students, evaluated primarily through PBATs, show higher college graduation rates than peers from traditional schools—even when those peers have higher SAT scores. The portfolio approach doesn't just predict college success; it prepares students for it.

To legislators, education officials, and policy leaders: Phasing out Regents exams was courageous. Now comes the harder part—implementation that realizes the vision. For statewide reform to succeed, policymakers should avoid tying accountability to high-inference CBA frameworks. Instead, they must examine what PBA easily provides: a validated record of a young person’s hardest work. This is the implementation that will empower young people and avoid mission creep into additional layers of bureaucracy. In other words, the most authentic portrait of a graduate isn't one drawn by administrators—it's assembled by the student, one substantial piece of work at a time.

For more information on performance-based assessment implementation and to see examples of student work evaluated through robust portfolio systems, visit the New York Performance Standards Consortium and HSCred.

Into Open Water

Feb 26, 2026

Professors, Not Permissions

Feb 1, 2026

Organic Leadership: A Perfect Principal Is a Paralyzed Principal

Jan 31, 2026

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HSCred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

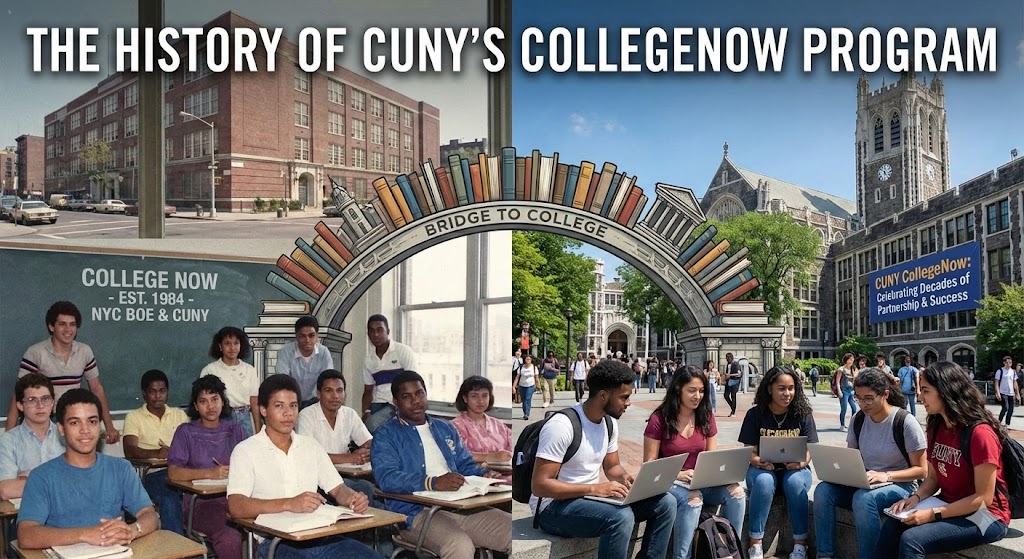

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025