Feb 1, 2026

By Nadav Zeimer

Something clicked last week that changed everything about how we talk about HS Cred. We stopped using the word "credit." It just didn’t accurately represent our model from the university vantage point. Since I’m a former high school principal, credit made sense to me. But I didn’t fully understand how severely university professors bristled at that word.

It first happened during a conversation with a professor who was trying to understand what we were asking her to do. And it kept happening. Next was direct feedback from a university administrator who asked for a word other than “credit” to describe the product to his team. I found myself reaching for analogies from their world, not the K-12 world.

"HS Cred acts like an academic journal, only we publish the research of high school students as videos. All you are doing at the university is choosing which pieces get published. You set the criteria. You recruit expert peer reviewers to provide multiple objective evaluations of each student project. Students submit their polished videos showing their academic thinking. If it meets your criteria, it gets published." Professors started nodding instead of shaking their heads.

The word "credit" had been getting in our way even before we started pitching to university professors. Google search results grouped us with financial institutions and we had to appeal to Alphabet to fix this miscategorization. The first donor we ever had complained about the search results that showed up around us for scam financial offerings.

Credits are what registrars manage. Credits are bureaucratic units. Credits trigger legal departments and comptroller offices and questions about transfer agreements. Heads shaking back and forth. Credits sound like we're asking institutions to certify something, to put their stamp on a student's record in ways that make general counsel nervous. They think of liability and are forced to agree that ‘no’ is their response.

Then I realized that we don’t want any of that permission structure. In fact, it limits what we are trying to achieve. What we are actually up to is much more accurately described as "published work” than “credit.” Since that is what professors already use to give academic evaluations of their peers, they understand how this can be used to evaluate the academic endeavors of high school graduates. “How many articles did they have published? Which journals?... Yes. Yes. That makes perfect sense.”

Professors serve as editors for journals as a routine part of academia. They review grants. They recruit peer reviewers. They decide what meets the criteria and what doesn't. They do this as a network of individual, “peers,” not controlled by any centralized authority. Not by any single university nor working for one single publication or review board. They represent their own expertise and nothing more. This decentralization is what gives academic peer review such power in practice.

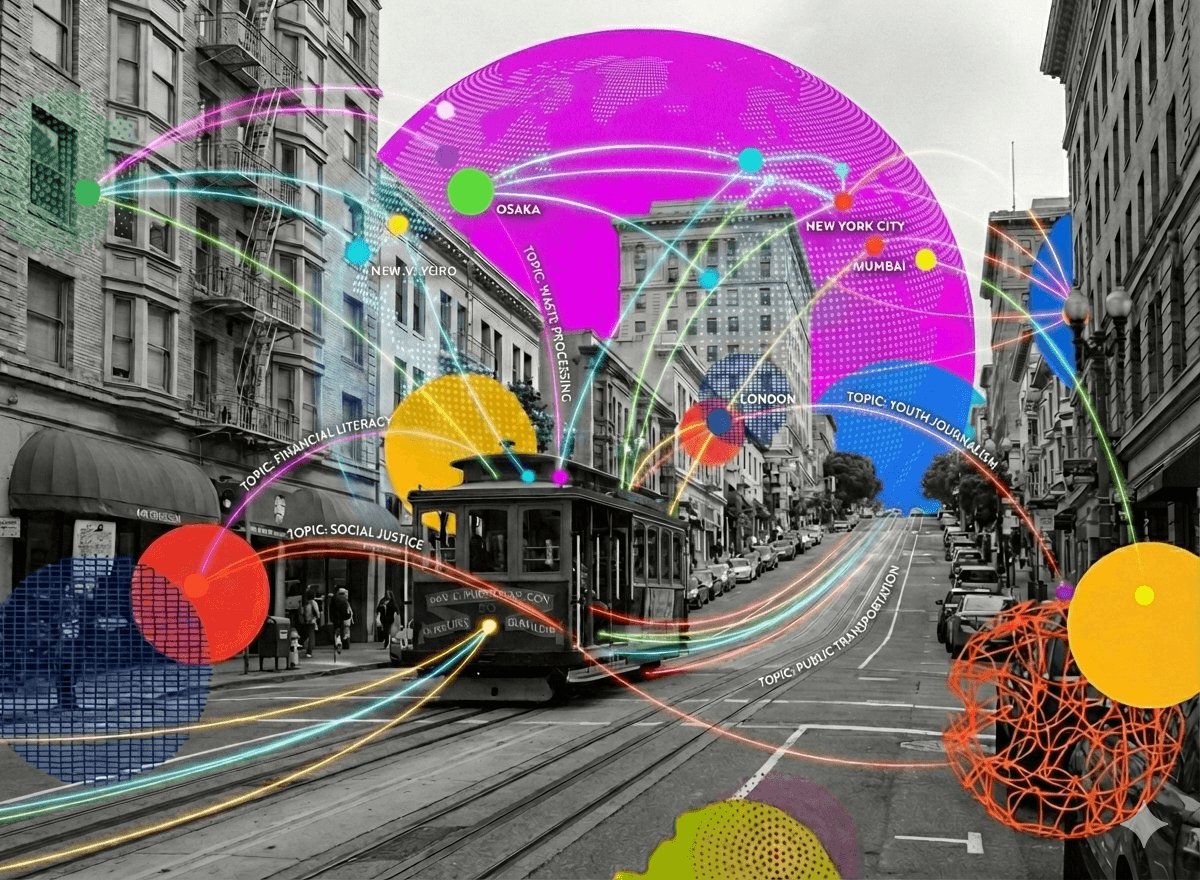

By listing their institutional affiliation the way any academic does, HS Cred could onboard professors without anyone assuming that CUNY or Osaka University has formally endorsed the particular video being reviewed. The institution provides context, certainly, but requires no permission.

This is the breakthrough that makes HS Cred scalable in ways we couldn't achieve through the front door of university admissions. A decentralized network of professors and their self-appointed peers is much more creative and responsive than any centralized league of ancient bureaucracies.

Consider what happens when an education technology company tries to partner with a university. First you need a meeting with someone in a dean's office. Then legal review. Then procurement. Then a pilot proposal. Then committee approval. Then budget allocation. Then integration with existing systems. The timeline stretches to years. Most initiatives die in those hallways, not because they lack merit but because institutions move slowly and have limited appetite for institutional risk. Anyone who has tried to innovate in education knows this dance. It's exhausting, and it means that good ideas get bottled up while students who could benefit wait for permissions that never come.

We decided not to dance. We built something that works the way academic publishing already works so well. A professor anywhere in the world can become what we're calling a Channel Editor. We should use the word Journal instead of Channel, but since the medium is video instead of text we upgraded the language to match the students’ digital context.

A professor defines the rubric for what counts as college-ready work in their domain. They recruit an Expert Panel of colleagues who will get paid to review student submissions. When a student submits a ten-minute academic video and it meets the criteria, it gets published to that Channel. The student's work becomes part of a permanent, portable record. The professor's name and affiliation appear as the Editor-in-chief, exactly as it would on any journal masthead, although this feels more like a YouTube channel, with carefully crafted and polished academic work of 11th an 12th grade students.

No institution has had to approve anything. An individual scholar has simply done what scholars do: set criteria, evaluate work, and decide what merits publication. This is not a workaround. This is how knowledge has been validated for centuries.

The first two editorial teams are forming right now. At the City College of New York, staff from the CCNY STEM Institute are creating the first HS Cred channels. At Osaka University in Japan, Professor Tamaki Akiko is doing the same with a Tankyu channel of her own. Professors see an opportunity to offer high school juniors and seniors the same respect they offer to each other as college professors; an opportunity to get published.

A chance to define what "ready" looks like in their field, thus impacting what students are spending their time studying in high school. Student work, evaluated by experts they trust, without waiting for their institutions to navigate the politics of a formal partnership.

The Japanese context makes this particularly vivid. Japan mandated inquiry-based learning for every public high school student, but the work doesn't count for anything when students apply to university. It floats in a protected bubble, disconnected from stakes. Often not evaluated formally at all! The reason is fear: if inquiry "counts," then cram schools will game it, and authentic learning will devolve into performance theater. This fear is not irrational. It's exactly what happened to standardized testing in America, where teaching to the test hollowed out curriculum, limiting it to what fits on an answer key when so much of life does not. Japanese educators watched that happen and resolved not to repeat it.

But the Channel model offers a different path. When a professor in Osaka becomes an Editor of her own channel on HS Cred, she's not creating a new test that can be gamed. She's creating a publication venue with public criteria. The work is visible. The rubric is visible. Income incentives drive the reviewers to strive for an objective distance from our all-too-human prejudices and emotional reasoning.

Any student at any school can submit work for publication. This levels the playing field across all types of high schools. A student who produces work that satisfies academic criteria gets published. There's no hiding behind manufactured polish when the artifact itself is the evidence. Either you can make your thinking visible on a recording or you cannot. Either your research holds up to scrutiny or it does not. The transparency is the protection against corruption. Start admitting low grade thinking and your channel becomes low grade, automatically, because everyone is watching. Students will then choose other channels that are respected by admissions offices because they benefit from a channel that maintains its academic integrity.

What excites me most is what happens when this network grows. Every new Editor brings their own expertise, their own standards, their own sense of what matters. A professor of environmental science might create a Channel for student investigations of local ecosystems. A historian might create one for documentary projects exploring primary sources. A mathematician might create one for students who can explain their problem-solving process, not just arrive at correct answers. None of these professors needs permission from anyone except themselves. They are exercising judgment the way academics have always exercised judgment. Students get access to validation that would otherwise be reserved for those lucky enough to attend schools with existing connections to university faculty.

This is the part that feels genuinely new. For decades, the students who benefited from performance-based assessment were students at elite schools or specialized programs. The New York Performance Standards Consortium built something remarkable, but it serves thirty-eight schools out of thousands. Big Picture Learning created apprentice-based learning that transforms lives, but it requires structural innovation that most districts cannot replicate quickly. The brilliant work happening in these networks has remained locked inside them because there was no infrastructure to carry it beyond school walls.

Now there is.

A student at a rural school in Mississippi can submit work to the same Channel as a student at a prep school in Manhattan. Both get evaluated against the same rubric by the same Expert Panel. Background recedes. What remains is evidence of thinking. The professor reviewing the work doesn't know what neighborhood the student lives in. They see ten minutes of explanation, analysis, demonstration, discussion. They score it. If it's good enough, it gets published. If it's not, the student revises and tries again. The only thing that is measured is the work itself.

The best part is that we're no longer pitching admissions offices. We're not asking them to change their processes. We're not selling them on a new digital platform. We're building something that will eventually arrive on their desks whether they expected it or not, carried there by students who include a link to their published work in their applications. The admissions officer will click the link. They'll watch a student explain a research project for two minutes. They'll think: this tells me more than any essay or test score ever could. And then they'll start asking questions. Not because we convinced them in a sales meeting, or because their president made it a strategic priority, but because the evidence convinced them. They ate the proverbial pudding of proof. And it was good.

That moment of discovery is what we're building toward. Journals don't need permission from the institutions that eventually cite them. They publish excellent work, and the world notices. Reputation accretes around quality. Trust follows evidence. We're borrowing that mechanism because it already works. It has worked for centuries across every scientific discipline and every country on earth. The innovation is not the peer review model. The innovation is applying it to high school work at the exact moment when the old signals are failing and everyone is searching for something better. As one professor commented after learning about HS Cred, “why has it taken us so long to start this?”

The vocabulary matters here because vocabulary shapes what people think is possible. When we say "Channel" instead of "credit" and instead of “journal” professors hear something that makes sense to them. When we say "Editor" instead of "proctor," they hear something dignified. When we say "Expert Panel" instead of "grading committee," they hear something that respects their expertise rather than conscripting it into bureaucratic compliance. These aren't marketing terms. They're accurate descriptions of roles that already exist in academic culture. We're just extending those roles to include student work that deserves serious attention.

The students we're about to onboard will be the first to build academic records through this system. They will be the first to choose which channel to seek publication with. Some of them are already producing excellent work in their classrooms, work that gets a grade and then vanishes. Others will create something specifically because they know a real audience is watching on HS Cred, an Expert Panel that includes scholars they admire, then guests to the platform that could be their family or a university dean. Students own a permanent transcript of published work that travels with them wherever they go.

What should college freshmen already know? That's the question on our postcard for professors. It's not rhetorical. It's an invitation. If you have strong opinions about what students ought to be able to do before they arrive in your classroom, build a Channel that publishes the students who can do it. Don't wait for curriculum committees to catch up. Don't petition administrators to revise graduation requirements. Create the publication venue yourself on HS Cred. Stock it with colleagues you trust to evaluate submissions fairly. Watch the work come in. Publish what deserves to be published. Let the students carry that evidence forward into a world that desperately needs better signals of readiness.

The day admissions officers discover HS Cred won't be the day we finally secured institutional permission. It will be the day they realized their permission structure was the problem. Scholarship has always spread through networks of individuals who care about quality, not through top-down mandates from bureaucrats. We're returning to that model now because students cannot afford to wait while institutions debate whether innovation is safe enough to replace tests we know too well are doing great damage to their #PassionForLearning.

Organic Leadership: A Perfect Principal Is a Paralyzed Principal

Jan 31, 2026

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

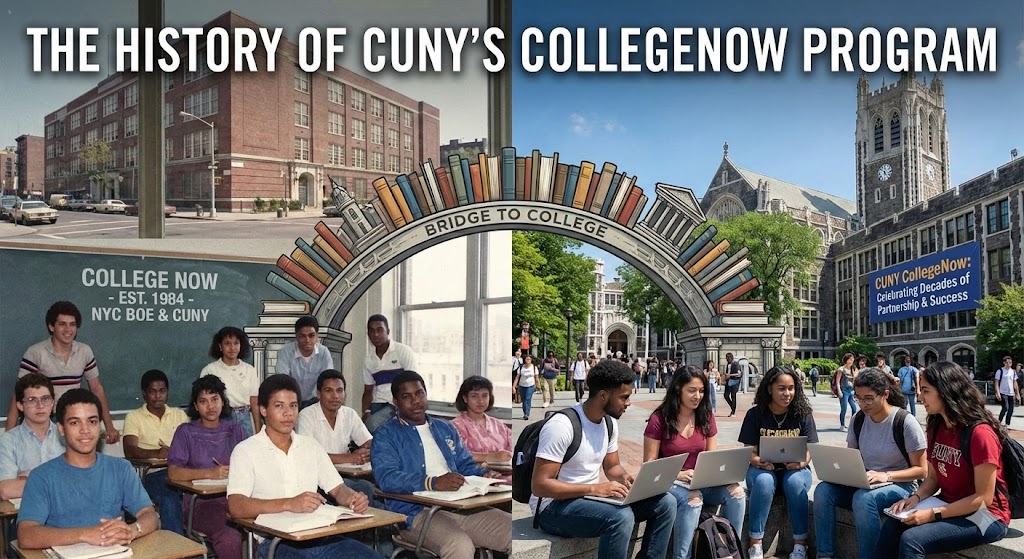

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025