Oct 20, 2025

The Empire State, which helped invent the high school exit exam for the industrial age, is now—more than a century and a half later—dismantling its grip. The revolution has been propelled by a parent revolt, a decade of policy overreach, and the quiet success of a network of small, alternative schools that never stopped asking students to show their thinking.

On a warm July day in Albany in 2025, the New York State Board of Regents advanced a vision that had been fermenting for years: a statewide shift toward a Portrait of a Graduate. Led by Chancellor Lester W. Young, Jr. and Commissioner of Education Betty A. Rosa, the Regents embraced the idea that young people should prove readiness through rich, authentic work—projects, presentations, research, and community engagement—not solely through timed, standardized exams and speed essays. In late July, the Department underscored that the work to implement the Portrait would continue through rulemaking and field guidance.

The timing carried a historical echo. Almost exactly 161 years earlier, on July 27, 1864, an earlier Board of Regents—under Chancellor John V. L. Pruyn—authorized uniform examinations to bring order to a patchwork system of “academies” and uneven standards. The first preliminary Regents examinations were administered in November 1865 to eighth graders; high‑school Regents followed in June 1878 and quickly expanded to cover subjects from algebra and American history to astronomy, rhetoric, and political economy. The state had, in effect, invented the high‑school exit exam—and with it, a powerful idea: a common yardstick for a modern, industrializing democracy.

New York led once, diving headlong into the logic of standardization. It is trying to lead again, this time away from factory‑era measurements and into a digital‑native era of learning by doing. The “gold standard” has changed. The ambition has not.

From Standardizing the Exam to Standardizing Judgment

Mid‑19th‑century schooling was a maze. Individual colleges ran their own entrance exams; there was no common curriculum and little way to compare students across towns. The Regents ordinance of 1864 solved a practical problem and carried a democratic promise: students who passed the new state exams would receive a certificate “entitl[ing] the person holding it to admission into the academic class in any academy…without further examination.” It was a portable credential—an early, state‑backed pass that smoothed entry into advanced study.

The choice matched the moment. As railroads standardized gauges and cities synchronized time, schools sought uniformity, too. By the late 1870s, New York’s Regents system offered dozens of subject tests and a shared language of merit—administered, importantly, by public authority. For generations, a Regents Diploma was synonymous with rigor, a reliable signal to colleges and employers alike.

Fast‑forward to July 2025: under Young and Rosa, the Regents adopted the Portrait of a Graduate—a framework that defines what every graduate should be able to do, not just what they can recall. It emphasizes communication, critical thinking, creative problem‑solving, cultural responsibility, and academic preparation, and it sits within a broader agenda (NY Inspires) to transform instruction, expand real‑world learning, and redesign quality assurance around student work. The reformers of 1864 and the reformers of 2025 share a through‑line: both moments tried to make admissions and advancement more legible and fair. In the 19th century, the instrument was a uniform exam; in the 21st, it’s a uniform way to judge authentic work with an authentic audience.

How the Single‑Exam Era Rose—and Frayed

The late 1990s brought a national push for tougher standards. In New York, that energy became Regents‑for‑All—a plan launched under Chancellor Carl T. Hayden and Commissioner Richard P. Mills to align the entire state to common learning standards and phase out the old “local diploma” in favor of passing Regents exams across core subjects. The rationale was compelling—equity through high expectations. But in practice, pressure changed classroom life. Curricula narrowed. Teachers learned to “teach to the test.” Families with means quietly built a test‑prep economy around tutoring and item‑type strategies. Meanwhile, high‑need schools felt the full weight of consequences tied to a few test days.

Investigations and audits found credit‑recovery shortcuts, on‑site grading concerns, and other distortions as graduation metrics became high‑stakes currency. In 2011–13, reporting and audits documented how some high schools leaned heavily on abbreviated make‑ups to inflate credit counts, prompting crackdowns on credit recovery and a shift to off‑site Regents scoring to reduce conflicts of interest. The students the policy most hoped to benefit—English learners, students with disabilities, and over‑age, under‑credited youth—often found themselves struggling under uniform exam requirements. The tests had become less a measure of thinking than a sorting device.

Two federal waves raised the stakes. No Child Left Behind (2002) mandated annual testing with sanctions for falling short; Race to the Top (2010) dangled competitive funding for states that adopted new standards, tests, and teacher evaluations tied to student scores. New York’s leadership in the early 2010s—Chancellor Merryl Tisch and Commissioner John King—pressed hard into the Common Core era with an evaluation system that made state tests consequential far beyond the classroom. In spring 2015, a grassroots opt‑out rebellion erupted. Led by organizers such as Long Island’s Jeanette Deutermann, more than 200,000 parents—roughly one in five eligible students—refused the grades 3–8 state tests, the largest boycott of its kind in the country. The public legitimacy of a single‑test gate was cracking.

Proof of Another Way: Alternative & Transfer Schools and the CUNY Signal

New York has long harbored a different tradition—small, relationship‑intensive schools that measure learning by what students can build, argue, and defend. In the early 1990s, under Commissioner Thomas Sobol’s “Compact for Learning,” the state invited innovative schools to mentor struggling ones and to experiment with performance assessments. That opening, together with the work of frontline educators including Ann Cook and colleagues, gave rise to the New York Performance Standards Consortium—a network that developed Performance‑Based Assessment Tasks (PBATs) in place of most Regents exams, and won a state waiver to use them.

A PBAT isn’t a packet of worksheets. It’s a months‑long inquiry culminating in a paper, lab, or proof, presented to and defended before external evaluators—a public demonstration of thinking. Over time, the Consortium built the professional infrastructure—shared rubrics, calibration protocols, and external moderation—that would let outsiders trust those judgments across schools.

At the same time, New York City’s transfer high schools—designed for students who were off‑track for graduation—grew into a safety net and a proving ground. Beginning around 2005, the city’s Office of Multiple Pathways to Graduation supported re‑engagement schools that paired capstone work, internships, and “relentless care” with targeted credit recovery done right. External audits in the Bloomberg/Walcott era exposed bad credit‑recovery shortcuts in some corners of the system—but they also documented how calibrated, teacher‑led performance assessments could maintain rigor even under pressure. These schools lived the central argument of today’s reform: that complex thinking leaves traces in student work a scantron can’t see—and that those traces can be judged fairly if the work is public, evaluated by multiple readers, and grounded in shared criteria.

Beginning in 2015, the City University of New York (CUNY) partnered with the Consortium to admit students based in part on their PBATs and teacher judgments, even when standardized scores fell below typical cutoffs. Researchers Michelle Fine and Karyna Pryiomka tracked outcomes and found that these students earned higher first‑semester GPAs, completed a larger share of credits, and persisted at higher rates than comparable peers. The pilot spurred CUNY to build admissions capacity to receive authentic student work—a concrete sign that validated performance can supply a higher‑resolution signal of readiness than test snapshots, especially for students whom standardized metrics tend to undervalue. This was the Consortium’s most important victory: not in court, but in the data—and in the changes one of the nation’s largest public university systems made in response.

From Blue Ribbon to Portrait: Minting a New Common Currency

By 2016, Regents member Betty A. Rosa—long critical of overtesting—had been elected Board Chancellor; she later became Commissioner, a rarity that concentrated both policy vision and implementation authority in a single, reform‑minded educator. In 2019, the Regents convened a Blue Ribbon Commission on Graduation Measures to ask a first‑principles question: What should a New York diploma mean now? Public feedback sessions teemed with calls for performance‑based assessment. In late 2024, the Department unveiled NY Inspires, a plan to sunset mandatory Regents exam pass‑scores as the sole graduation gate and to expand rigorous alternatives aligned to a Portrait of a Graduate. In July 2025, the Board formally adopted the Portrait, and state officials reiterated that implementation would phase in with attention to quality assurance. Notably, the plan drew public support from NYSUT, the statewide teachers union.

It’s tempting to frame this as a break with 1864. In a deeper sense, it’s a rhyme. Before the Regents exams, each college ran its own entrance tests. The 1864 ordinance created a common certificate that any academy recognized, no additional test required. Today’s reformers are trying something parallel: standardize the validation of local, authentic work, not the tasks themselves. While standardized testing was brutal to human love of learning, their system of impartial evaluators was important and must not be abandoned. In the 1860s, the state certified scores; in the 2020s a decentralized community of university staff and any other educators they certify will do so. The culminating project a student defends in Buffalo can be trusted as much as the one defended in Brooklyn because both were judged against shared, public criteria by paid impartial evaluators. Recorded proof‑of‑work replaces bubble sheets. Encouraging a general public to verify the quality of published student work. Rounds of supervised feedback and revision replace speed essays and exam proctors.

The Portrait articulates a graduate who can reason carefully, communicate effectively, create solutions, engage ethically across cultures, and contribute to community life—and who is academically prepared to take the next step. Those words can sound airy until you sit across from a teenager defending a history paper before outside reviewers, or watch a student explain the design choices and error bounds in a self‑authored science experiment. What the Portrait insists on is visible cognition—students showing how they know, not just what they know.

To make that real statewide, the Department has proposed capstones and real‑world learning opportunities, alongside a quality‑assurance system to validate the work. It is a shift from regulating inputs (what everyone teaches) and single‑day scores to regulating the fairness and comparability of judgments about student work. The hard work isn’t designing projects; it’s building moderation and external review so that public judgment is comparably exacting across districts. New York can borrow from the Consortium’s moderation studies, from university pilots, and from other states’ performance‑assessment collaboratives.

Student buy‑in. The essential element is student choice. Regents exams will remain an option during the transition; they will only fade if students choose the performance pathway. That demands excellent user design—the submission, feedback, and defense experience must feel worth a teenager’s effort. Experts like Al McCutchen and thoughtful product design will matter so that students find it convenient and meaningful to submit their best academic work.

The Board’s adoption of the Portrait is final; the phase‑out of Regents pass‑scores as a universal graduation gate is proceeding through rulemaking and phased implementation under the NY Inspires plan. Students will still be able to take Regents exams—they will be one option among several—and the “sunset” would occur over several years if formally adopted. Leadership matters: the current Chancellor (Lester W. Young, Jr.) and Commissioner (Betty A. Rosa) have been central to moving the system from concept to policy, echoing the role the 19th‑century Regents played in creating a common credential.

Stand back and the parallel snaps into focus. In the 1860s, New York standardized the measure—the exam—and became the nation’s reference point for high‑school rigor. In the 2020s, it is trying to standardize the validation of complex work—turning projects, labs, and defenses into public acts judged against published rubrics by trained evaluators, with a paper trail colleges can read. In a sense, the system is inching back toward the pre‑Regents world of institutional judgment—colleges once examined applicants themselves—while preserving the cross‑institutional portability the 1864 Regents promised. In the CUNY pilot, admissions evidence was curated by schools with strong internal validity; CUNY even adapted its platform to accept student work as part of a holistic review. That is how a “local” judgment becomes publicly legible again. If the state can build the moderation and external‑review infrastructure, it won’t just have replaced a set of tests; it will have minted a new kind of academic capital—evidence of thinking that travels.

The (Careful) Road Ahead

A reform this large sits in cross‑currents. Equity advocates argue that a single test gate amplifies inequality; accountability hawks worry that flexibility breeds grade inflation. Teachers and their unions—burned by the test‑and‑punish decade—fear a swap from one paperwork burden to another. The answer lives in quality assurance and resourcing, not in rolling back the vision: the state will need regional moderation, randomized audits, and public reporting of task quality and scoring reliability. It will need time in the calendar and dollars in contracts for teachers to meet, score, and recalibrate. And it will need higher‑education partners to honor this work in admissions and placement, as CUNY has begun to do. The opt‑out movement supplied the democratic legitimacy to move; the Consortium and transfer schools supplied the technical know‑how; and the CUNY pilot supplied the empirical proof colleges needed to trust portfolios of externally validated student work. Put differently: the politics, the craft, and the data finally lined up.

The Portrait is the blueprint. The scaffolding—the comparability, the moderation, the digital infrastructure to move student work across institutions—will decide whether the promise sticks. Today, surprisingly few platforms translate capstones into portable, verified credentials. One, HSCred, created at a Transfer School in Central Harlem, is piloting tools that let students bank externally validated presentations as digital credentials that admissions offices can read alongside transcripts—a modern echo of the 1864 promise that a recognized credential should travel. It’s not the only approach, and it will need to prove its reliability and equity at scale. But as New York trades the scantron for the public defense, tools like this are likely to be part of the next chapter, providing an authentic audience and external validation for participating students—even before their schools fully adopt the model. This is a student‑centered initiative, built on their sweat equity.

If New York pulls this off, it will have led the nation twice—once into the age of standardized exams and once out of it.

Sources and Further Reading

History of Regents Exams (official NYSED history, includes the 1864 ordinance, 1865 “preliminary” exams, and 1878 high‑school exams)

Timeline of NY State assessments (official NYSED)

Portrait of a Graduate (NYSED news page announcing adoption, July 31, 2025)

NY Inspires plan (implementation roadmap for graduation‑measures changes):

Graduation Measures FAQ & “sunsetting” diploma assessment requirements (NYSED)

Summary page (see links to FAQ); and the dedicated FAQ with cohort timeline

EdWeek overview of states (including NY) moving to reduce/diffuse exit exam gatekeeping

NYSED press release & Regents materials when the Blue Ribbon Commission presented its recommendations (Nov. 13, 2023):

Opt‑Out movement (2015)

New York Times coverage of the 2015 refusal wave: About 20% of students statewide refused the 2015 grades 3–8 tests (Aug. 12–13, 2015).

Chalkbeat on the organizing and scale (school‑by‑school numbers & Long Island organizing):

“Tripling in size, city’s opt‑out movement draws new members but anger remains focused on Albany” (Apr. 9, 2015):

Credit recovery & accountability distortions (2011–2013)

Chalkbeat investigations and policy changes: “City alters Regents grading, credit recovery policies after audit” (Feb. 24, 2012)

“With stricter credit recovery policy comes a push to do more” (Mar. 19, 2012):

“Use of ‘credit recovery’ in city schools varied widely, data show” (Sept. 24, 2013): ;

Early probe example: “As principal departs, investigation at Randolph stays behind” (Dec. 2, 2011):

Alternative & Transfer schools (NYC Multiple Pathways)

EdWeek explainer with data from NYC’s Office of Multiple Pathways (2007): “Pathways to a Diploma” (Apr. 2007):

Hechinger Report (history of OMPG and expansion of transfer schools/YABCs): “New York City: Big gains in the Big Apple” (context on 2005 OMPG launch):

MDRC’s evidence on NYC small schools/transfer‑sector context:

Project hub: and report “Transforming the High School Experience” (2010):

Recent field synthesis on transfer schools (NYU Metro Center): “Recuperation and Innovation: New York City’s Transfer High Schools” (2023):

Consortium & performance‑assessment research

Consortium website (model, PBATs, history, CUNY pilot):

The 2000 fight over waivers (national reporting at the time): EdWeek, “N.Y. Chief Deals Blow to Alternative‑Assessment Plans” (Mar. 29, 2000):

Learning Policy Institute national synthesis & case studies:

The Promise of Performance Assessments: Innovations in High School Learning and Higher Education Admissions (2018):

CUNY–Consortium admissions pilot outcomes (Fine & Pryiomka): LPI report: Assessing College Readiness Through Authentic Student Work (2020):

Union & other stakeholder positions

WXXI (public media) on NYSUT’s support for the proposed shift (including quotes and counter‑positions from EdTrust‑NY):

“New graduation requirements proposed by NYS education department would ‘sunset’ Regents exams” (June 14, 2024):

Follow‑up local coverage as Regents voted to adopt the new framework (July 2025):

“High school requirements will look different in a few years. Here is what’s changing” (July 16, 2025):

Bonus: A few additional pieces you may find useful

Chalkbeat on the Consortium as the state rethinks graduation requirements (great overview):

NYSED “Graduation Requirements” summary page (current rules while changes phase in):

Into Open Water

Feb 26, 2026

Professors, Not Permissions

Feb 1, 2026

Organic Leadership: A Perfect Principal Is a Paralyzed Principal

Jan 31, 2026

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HSCred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

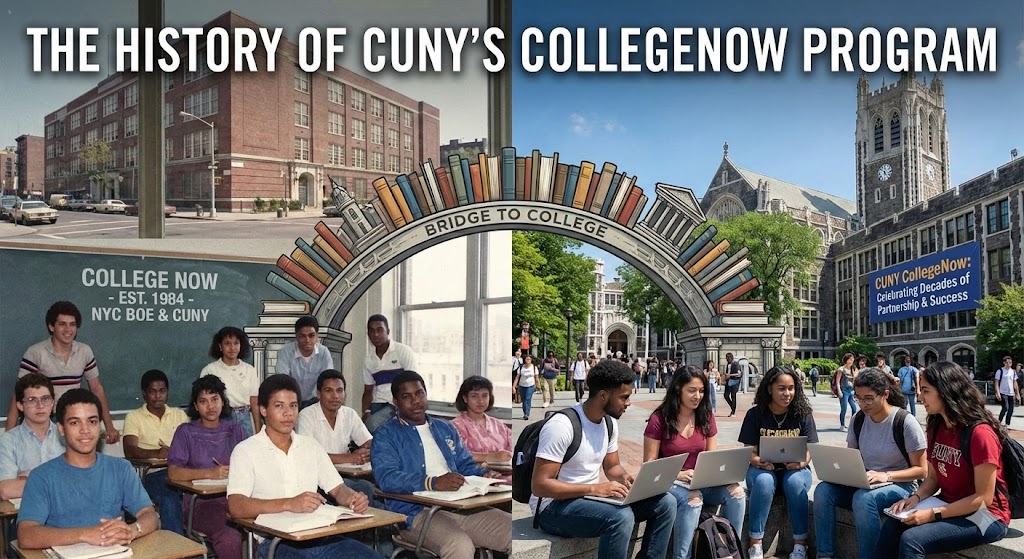

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025