Dec 2, 2025

By Nadav Zeimer

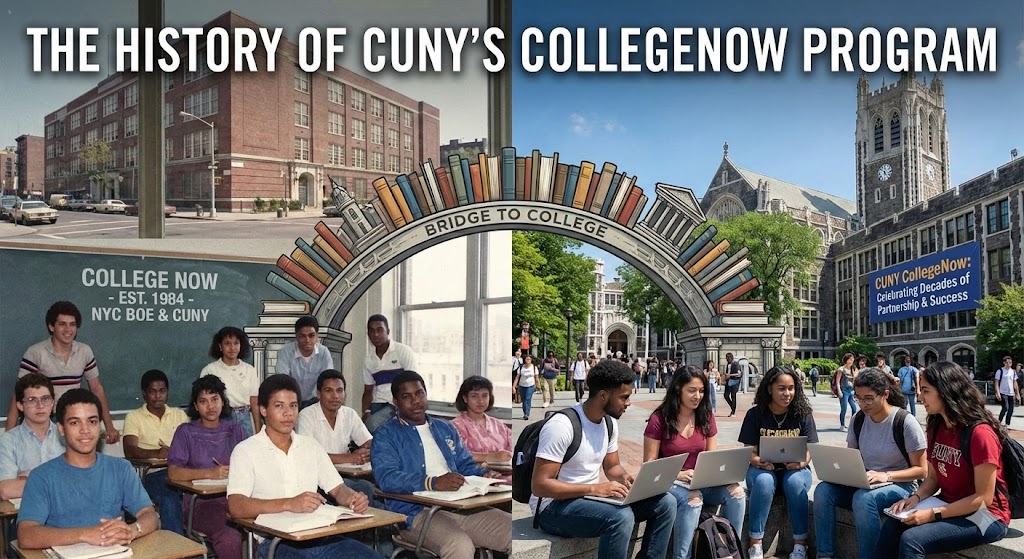

If you're a high school administrator in New York City, College Now is probably a familiar institution. It's the trusted dual-enrollment pipeline—the program that lets students walk into a CUNY classroom before they've thrown their caps in the air.

But here's what you might not know: before College Now became a citywide institution, it was a radical gamble launched by one Brooklyn community college president who got tired of waiting for the system to change.

To understand where we're heading with Academic Capital at HS Cred, it helps to look back at the program that proved, forty years ago, that high school students are capable of far more than anyone was giving them credit for.

1984: A Brooklyn Experiment

In the early 1980s, high schools and colleges operated in separate universes. Principals didn't lunch with provosts. The idea of teenagers sitting in college classrooms was, at best, a curiosity reserved for a handful of prodigies. Then came Leon M. Goldstein.

Goldstein was the president of Kingsborough Community College, and he had a front-row seat to a frustrating pattern: students would graduate from nearby Brooklyn high schools, enroll at Kingsborough, and immediately land in remedial courses. They weren't stupid—they just hadn't been prepared. Goldstein decided to stop waiting for the problem to arrive at his door.

In the spring of 1984, he launched a pilot with 449 students from four Brooklyn high schools. The pitch was simple: come to campus, take real college courses, earn real credits—for free.

The results surprised everyone. Principals noticed something strange happening with their seniors: kids who normally sleepwalked through their final semester were suddenly showing up early. At Kingsborough High School, students like Maria Pak and Eric Radezky started arriving 50 minutes before the first bell—not for detention, but for a three-credit science class. Radezky told reporters he loved being "treated like an adult and like a college student."

Within five years, the experiment had spread to 17 high schools. Goldstein had demonstrated something the system had long overlooked: when you raise expectations and treat students as scholars, they rise to meet you.

The 1990s: From Nice-to-Have to Necessity

By the 1990s, College Now had evolved from an interesting pilot into something more urgent: a potential solution to a crisis. When CUNY launched its Open Admissions policy in 1970—guaranteeing every NYC high school graduate a spot in the university—administrators expected growing pains. What they got was a tsunami. In that first fall semester, roughly 25% of incoming freshmen tested at or below a ninth-grade reading level. Remedial courses multiplied. Costs ballooned. And the problem didn't go away.

By 1997, over half of CUNY's freshmen were still failing the university's reading exam. CUNY Board Chairman Herman Badillo and other reformers recognized an uncomfortable truth: you can't fix college readiness in the freshman year of college. You have to start in high school.

College Now offered a proof of concept. It wasn't just about high-achievers padding their transcripts—it was about early assessment, targeted support, and giving students authentic college-level work before they ever matriculated. In 1998, with state and city backing, CUNY replicated the Kingsborough model at five more community colleges.

The blueprint was set: test students in 11th grade, support those who need it, and put those who are ready into real courses.

2000: Two Chancellors, One Bet

The turn of the millennium brought the moment when College Now stopped being a program and became policy. In a rare alignment of institutional will, CUNY Chancellor Matthew Goldstein and NYC Schools Chancellor Harold O. Levy decided to go all in. On February 7, 2000—with Badillo at their side—they announced a citywide expansion.

The ambition was staggering. They planned to scale from six campuses to all 17 CUNY undergraduate colleges, partner with 150 high schools, and serve 25,000 students—essentially overnight. Two of the largest bureaucracies in American public education would have to learn to work together.

There were stumbles. Some principals were skeptical of yet another initiative. Senior colleges worried about maintaining standards. Trust between the systems had to be built from scratch. But the numbers made the case. By 2002, enrollment had quadrupled to 40,000 students. College Now had become woven into the fabric of New York City education—surviving even the Bloomberg-era reorganization that transformed the Board of Education into today's DOE.

Where We Go From Here

Today, College Now is a national model. Educators from across the country study how New York pulled it off. But here's what made it work—and why it matters for what comes next.

College Now succeeded because it broke down barriers to college access—and redefined how potential gets demonstrated. A student's readiness wasn't just a test score or a transcript line; it was their ability to do actual college-level work. That was the revolution: not just access, but a new way for students to prove their skills experientially.

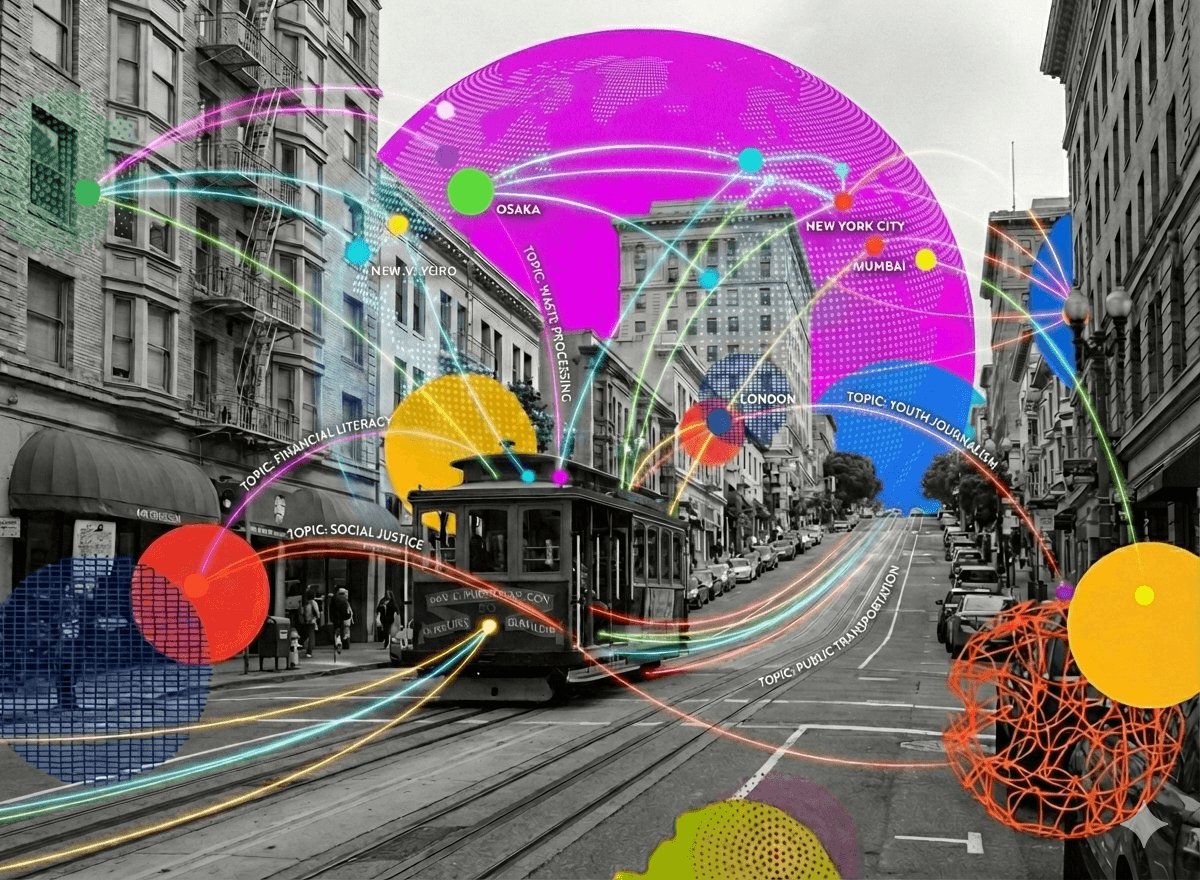

The success of this program proved that high schoolers are ready for a challenge. But College Now is bound by geography. A student needs to be near a CUNY campus, or their school needs a specific partnership agreement. Seat capacity is finite. In 1984, we didn't have the internet or digital platforms. Now that we do, students can connect with university faculty directly—no bus to Kingsborough required. That's the opportunity: earning credentials from any university, not just the one closest to your high school.

HS Cred is the digital evolution of the College Now spirit. Just as Leon Goldstein saw an opportunity to bridge the gap between high school and college in 1984, we see an opportunity to bridge the gap between student work and university recognition today.

By offering students access to credits published by universities worldwide, we're taking the logic of dual enrollment and removing the physical constraints. A student in the South Bronx can earn a university-validated credit from a school in California or even Osaka, Japan. A student in rural Mississippi can experience college work with direct access to faculty at any CUNY school who get paid to review student work.

College Now opened the door. Now it's time to knock down the walls entirely.

---

Sources: College Now program archives and reports; City University of New York publications; NYC Department of Education historical records.

Nadav Zeimer is the founder of HS Cred and former principal of Harlem Renaissance High School. He works with schools and universities reimagining how student achievement is recognized and validated.

Learn more at HSCred.com

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025