Jan 19, 2026

What Should Testing Look Like in an America Celebrating Freedom?

By Nadav Zeimer

On this MLK Day of Celebration for a 100+ year movement that secured the vote for former slaves (starting before the 15th Amendment in 1870 and past the 1965 Voting Rights Act). I take the liberty to celebrate a legend who helped make that historic movement a success. We have so much more work to do so that every single American has enough dignity to stand proud with basic human needs met, but the right to vote is more secure today than it has been in the past, if constantly under attack. On these days of celebration it is important to remember all those extraordinary freedom fighters who stood tall even before being afforded the right to basic human dignity.

In August 1964, a sharecropper from Sunflower County, Mississippi walked into the Credentials Committee of the Democratic National Convention. Fannie Lou Hamer had been beaten in jail for trying to register to vote. She had been thrown off the plantation where she had worked for eighteen years. Sixteen bullets had been fired into the home where she sought shelter. And when she finally got a microphone in front of the people who held power, she did not ask for permission or apologize for taking their time. She knew that she was a soldier fighting against the need to have soldiers. She told them what had happened to her in her fight for freedom, in her own voice, and then she asked a question that still echoes: "Is this America?" Fannie Lou loved America because she saw in us a common fight for freedom. Even when she had been denied it by so-called Americans. She never lost sight of an ideal she was fighting for: a land of freedom.

What made Fannie Lou Hamer an effective opponent was her refusal to let other people tell her story. She had been invisible her entire life in the eyes of mainstream culture—a Black woman in the Delta, picking cotton, existing in a system designed to keep her silent. When she finally spoke, she spoke for herself. "I didn't try to register for you," she told the plantation owner who demanded she withdraw her voter registration. "I tried to register for myself." What a force she was for the world to reckon with. A force that demanded our goodness rather than one that fights for anger and revenge.

And her story continues to echo in the stories of students at a school in the South Bronx that carries her name. Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School is not famous in the way that Stuyvesant or Bronx Science are famous. It does not appear on the lists that affluent parents circulate when their children approach high school age. It serves students from one of the poorest congressional districts in the United States, and it graduates them at rates that would make any school proud.

But what matters most is how it graduates them. At Fannie Lou Hamer, students do not prove their readiness by filling in bubbles on a standardized test. They have stories to tell in the legacy of their namesake. They write research papers and design science experiments and solve mathematical problems that have no single answer. Then they stand in front of panels of teachers and outside experts and defend their findings. They explain their thinking. They answer hard questions. They revise and return and revise again until the work is genuinely theirs. It is their own story of learning something complex. Their individual fight for intellectual freedom.

What FLHFHS does is not a new invention. It is part of the crown jewel that is The New York Performance Standards Consortium. A network of thirty-eight high schools that have been doing this for three decades. The students produce what the Consortium calls PBATs—Performance-Based Assessment Tasks—in literature, social studies, science, and mathematics. Performance-based assessment.

An analytic essay on a novel. A research paper on a question that emerged from class discussion, something like "Why did the Civil Rights Movement happen when it did?" An original experiment, designed and executed by the student, with data collected and analyzed and conclusions drawn. A mathematical narrative describing the journey through a non-routine problem, the dead ends and breakthroughs and reasoning that led to a conclusion.

The written work is substantial, but the oral defense is what transforms it. Students present to panels that include their own teachers, faculty from other schools, and community members. The format resembles a graduate thesis defense more than anything that happens in a typical high school. Evaluators use rubrics that have been developed and refined by practitioners over decades, and twice each year teachers from across the Consortium gather to compare student work and calibrate their judgments. The system is rigorous and transparent and publicly documented—the rubrics are available on the Consortium's website for anyone to examine.

When researchers from the Learning Policy Institute studied what happened to these students after graduation, they found something that has changed the national conversation about assessment. Students from Consortium schools—despite entering high school more economically disadvantaged than their peers, despite having lower average SAT scores—earned higher first-semester college GPAs, completed more credits, and persisted at higher rates than students from traditional schools. The correlation held across racial and economic groups. Black males from Consortium schools were dramatically more likely to stay in college than the national average for their demographic. A focus on student work was predicting success better than the tests that were supposed to measure readiness but (as it turns out) mostly sort by zip code.

The work of these students is the foundation that New York State's Portrait of a Graduate was built upon. When the Board of Regents voted to phase out Regents exams as graduation requirements, they were not abandoning rigor. They were recognizing what schools like Fannie Lou Hamer had proven: that authentic student work, evaluated by external assessors against public rubrics, produces graduates who are genuinely ready for what comes next. The framework was not theoretical. It emerged from practice. Teachers and students in these schools had already done the hard work of figuring out what performance-based assessment looks like at scale.

What remains missing is the infrastructure to make this work portable and scalable without additional burden on the educators. At HS Cred, we demand that students do the extra work to convert any of their final projects into a digital format for our digital audience. It is as if we are asking them to be journalists, reporting on their own learning experience, to present to colleges and universities. Their journey as scholars, memorialized.

We specifically leave the teachers and curriculum out of this - it is up to students to take the initiative to digitize their project and upload it to HS Cred to show that they go above and beyond their peers and what is mandated by the school. Asking a student to convert their 24 page research paper into a 10-minute video is like asking my generation to convert that essay into PowerPoint slides and a live presentation. Video is easier because kids can edit - they have control over the final product even more than when they present to a live panel of judges.

A student at Fannie Lou Hamer produces a research paper on the history of environmental racism in the South Bronx. She stands in front of a panel and defends her sources, her analysis, her conclusions. She responds to questions about methodology and evidence. She revises based on feedback and presents again. The process takes time. The final product represents genuine intellectual achievement—the kind of work that demonstrates exactly the competencies that colleges claim to value.

But when that student applies to college, what travels with her? A transcript with course names and grades. The nuance of that live presentation is lost. Perhaps a letter from a teacher. Maybe an essay that the admissions office will skim in two minutes, if they read it at all, wondering whether a consultant wrote it or whether AI polished it into generic fluency. The actual work—the artifact that proves what she can do—is lost. Unless she memorializes it as a video and uploads that video to HS Cred for evaluation by university staff.

The gap HS Cred seeks to close must be closed by the students first. Their hard work is what generates academic value which can then be digitized as a video. We want to celebrate what schools like Fannie Lou Hamer already do, by offering the most ambitious students a bigger audience. When a student records a ten-minute presentation of their work—showing the question they investigated, the process they followed, the evidence they gathered, and the conclusions they drew—that recording becomes a permanent digital artifact.

The validation happens through multiple layers. The supervising teacher confirms that the work is authentic, that it emerged from real cycles of feedback and revision, that the student standing behind the camera and final edit is the same person who struggled with the material over months.

Then three independent subject-matter experts—paid professionals with no relationship to the student or the school—evaluate the recording against public rubrics. They assess only what they see. The judgment is low-inference: does this work meet the academic criteria, or doesn't it? The consensus of four evaluators—teacher plus three external experts—determines whether the credit is awarded. But a much wider audience can see any credit channel for themselves whether they are considering a credit themselves or evaluating what kind of work is approved for publication by different academic institutions.

Students at Consortium schools have an enormous advantage in this system because they are already doing the work. A student who has completed a PBAT at Fannie Lou Hamer knows how to investigate a question, how to present findings, how to defend conclusions under questioning. Converting that work into a ten-minute video is not a new skill to learn. It is a different format for demonstrating what they already know how to do.

The classroom is like a newsroom of academic inquiry. The oral defense is already a performance. What changes is the audience—from a panel in a school building to an internet platform where the work can be seen and validated and carried forward into applications and opportunities. For students today, creating such a video is as easy as creating a powerpoint presentation was for my generation.

For educators in Japan who are watching the American experiment with great interest, this matters. Japan mandated inquiry-based learning for every public high school student, but the work does not count for university admissions. The fear is that connecting inquiry to high stakes will corrupt it—that cram schools will emerge to game the system, that authentic learning will devolve into performance theater. This fear is not irrational. It is precisely what happened to standardized testing in America, where teaching to the test hollowed out curriculum and where score gains often reflected test preparation rather than genuine learning.

But the Consortium schools offer a different model. The assessment is designed by practitioners who understand what real learning looks like. The rubrics are public. The evaluation involves multiple external assessors. The work is visible—anyone can look at what students produce and judge for themselves whether it represents genuine achievement. This transparency is the shield against corruption. When the artifact is published, when the reasoning is recorded, when the work speaks for itself, there is no hiding behind manufactured polish. Either the student can think, or they cannot. Either they understand their material deeply enough to explain it and defend it, or they do not. Wealthy students can always pay for a crutch to coddle them, but those who achieve these credits independently benefit for life from the experience itself.

Big Picture Learning, the network that includes Fannie Lou Hamer and over a hundred other schools, has been building toward this vision for thirty years. Their tagline is "one student at a time," and their approach centers on relationships, internships, and real-world learning. The school is not a factory processing students through standardized curricula. It is a community where each young person is known well and supported to pursue work that matters to them. The advisory system ensures that no student is overlooked. The extended learning opportunities connect classroom work to the world outside. The entire structure assumes that students are capable of far more than traditional schooling asks of them—and that when you raise expectations while providing genuine support, students rise to meet them. In fact, student engagement depends on high expectations since anything less is boring.

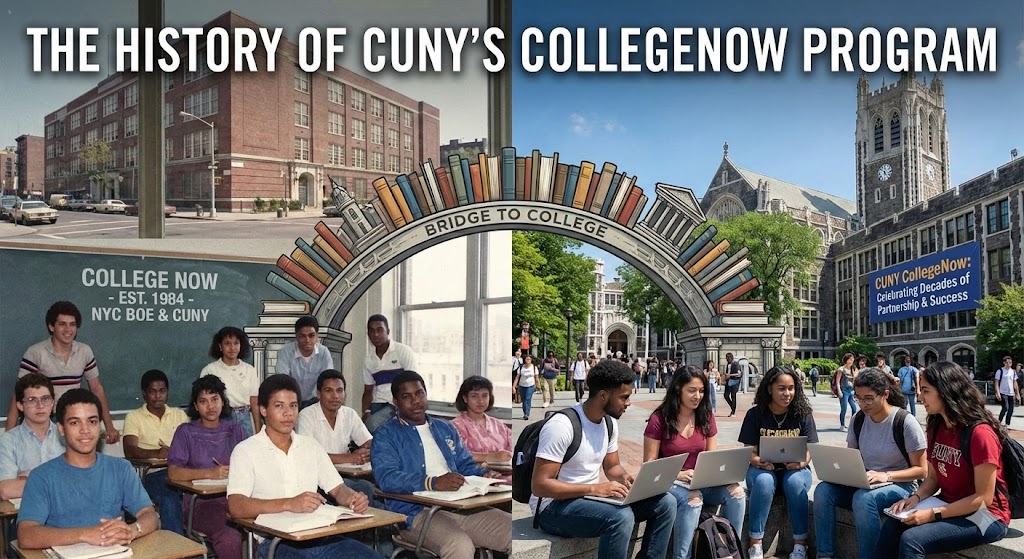

Next week at the Big Picture Learning Leadership Summit in Harlem, educators from across the country will gather to imagine what comes next for student-centered learning. The summit is well placed in New York City. This is where the Performance Standards Consortium proved that performance-based assessment could work at scale. This is where CUNY partnered with Consortium schools to admit students based on portfolios of authentic work rather than test scores. This is where the Portrait of a Graduate framework emerged from decades of practitioner knowledge. The city itself will be the teacher, as the summit organizers put it—a place defined by its energy, diversity, and constant reinvention.

What I see in schools like Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School is what Fannie Lou Hamer herself understood: that the most important thing you can do for people who have been silenced is to give them a microphone and get out of the way. The students at these schools are not being prepared to take tests. They are being prepared to speak for themselves. They learn to investigate questions that matter to them. They learn to build arguments from evidence. They learn to stand in front of adults and defend their thinking without apology. They learn, in other words, exactly what Fannie Lou Hamer learned in the cotton fields of Mississippi—that their voice matters, that their story is worth telling, and that no one else can tell it for them.

I am sick and tired of watching students get reduced to test scores. I am sick and tired of watching brilliant young people from under-resourced schools get overlooked because they lack the institutional stamp that validates their talent. I am sick and tired of an assessment system that measures compliance rather than capability, that rewards the students who have access to test prep rather than the students who have done the hardest thinking. The Portrait of a Graduate promised something different. The Consortium schools have been delivering on that promise for decades. What we are building at HS Cred is the infrastructure to make that promise digital—to ensure that when a student at Fannie Lou Hamer produces work that demonstrates genuine readiness, the world can see it.

The ten-minute video is not complicated. It asks students to do what Consortium schools have always asked: show us the question you investigated, show us the process you followed, show us what you learned, show us the proof. Record your thinking. Make it visible. Let the work speak for itself but to a broader audience.

For students who have been doing this work already, the conversion is straightforward. For students at schools that have not yet embraced project-based learning, it is an invitation to join a movement that has been building for three decades. Especially if you live anywhere in New York State. The rubrics exist. The models exist. The research demonstrating superior outcomes exists. What remains is the will to act on what we already know.

Fannie Lou Hamer did not wait for permission. She did not wait for the system to change before she demanded to be heard. She understood that some things cannot be given—they have to be taken. The right to vote. The right to speak. The right to be recognized as fully human, fully capable, fully present.

Students today face a different kind of exclusion. The gatekeepers are admissions offices rather than registrars of voters. The weapon of suppression is a standardized test rather than a literacy test. But the solution is the same: refuse to be silent. Produce work that cannot be ignored. Stand in front of people with power and demand that they publish your academic work.

The students at Fannie Lou Hamer Freedom High School already know how to do this. They have been practicing every semester, in every PBAT, in every oral defense. Now we are building the infrastructure to ensure that their work travels with them—that the excellence they demonstrate in the South Bronx can be seen and validated and recognized anywhere in the world.

Is this America? The testing surely is not a representation of a common commitment to freedom. But it can be if project-based learning expands because we began to measure outcomes using performance-based assessment. American education should be about each student’s voice. About their academic thinking that breaks the boundaries of any answer key. Increasingly, thanks to schools that carry the spirit of Fannie Lou Hamer into every classroom, it is becoming so.

In just a few weeks (February 2026) HS Cred will begin onboarding students who want to stand up and be heard. Join us as we hear what they have to say.

Nadav Zeimer is the founder of HS Cred, Inc. and a former NYC turnaround principal. The Big Picture Learning Leadership Summit takes place January 26-29, 2026 in New York City.

#PassionForLearning #AcademicCapital

テスト漬けの教育からの脱却

自由を祝うアメリカで、学力評価はどうあるべきか

2026年1月20日

ナダブゼマー

100年以上にわたる運動が、かつて奴隷であった人々に投票権をもたらしたこのキング牧師の日(マーテインルーサーキングJr.を祝うアメリカの祝日)に、私はその歴史を切り開いた一人の人物を讃えたいと思います。その運動は、1870年の憲法修正第15条以前から始まり、1965年の投票権法を超えて続いてきました。

すべてのアメリカ人が必要最低限な生活レベルを満たし、尊厳を持って生きれる社会を実現するには、まだまだやらなければいけないことがたくさんあります。しかし投票する権利そのものは、常に攻撃にさらされながらも、過去よりもはるかに守られたものになっています。こうした祝賀の日にこそ、基本的な人間の尊厳すら与えられていなかった時代から立ち上がり続けた、自由の闘士たちを思い返すことが大切なのです。

1964年8月、ミシシッピ州サンフラワー郡の小作農が、民主党全国大会の資格審査委員会の前に立ちました。彼女の名はファニー・ルー・ヘイマー。彼女は投票登録を試みただけで、留置所で殴打されました。18年間働いていた農園から追い出されました。身を寄せていた家には16発の銃弾が撃ち込まれました。そしてついに権力を持つ人々の前でマイクを手にしたとき、彼女は許可も謝罪も求めませんでした。彼女は、自分が「兵士を必要としない世界のために闘う兵士」であることを知っていたのです。

彼女は自由を求めて自分に起きたことを、自分の声で語り、そして問いかけました。「これはアメリカなの?」ファニー・ルー・ヘイマーは、私たちの中に共通の自由への闘いを見ていたからこそ、アメリカを愛していました。いわゆる「アメリカ人」から自由を否定され続けても、彼女は決して理想を見失いませんでした。自由の国のために戦っていたのです。

ファニー・ルー・ヘイマーがこれほど力強い存在であった理由は、他人に自分の物語を語らせなかったことにあります。彼女は、デルタ地帯で綿花を摘む黒人女性として、主流社会からは『見えない』存在でした。沈黙させるために設計された制度の中で生きてきました。しかし彼女が語り始めたとき、彼女は自分自身のために語ったのです。

「あなたのために登録したんじゃない。自分のために登録したんだ」

投票登録を撤回しろと迫った農園主に、彼女はそう言いました。なんという力でしょう。怒りや復讐を求めるのではなく、私たちの「善」を要求する力です。

そして彼女の物語は、今もサウスブロンクスにある彼女の名を冠した学校の生徒たちの中に響き続けています。ファニー・ルー・ヘイマー・フリーダム・ハイスクール(FLHFHS)は、スタイバサントやブロンクス・サイエンスのような有名高校ではありません。裕福な家庭の親たちが共有する『良い』高校リストに載ることもありません。全米で最も貧しい選挙区のひとつに住む生徒たちを受け入れながら、誇れる卒業率を実現しています。

しかし、最も重要なのは「どうやって」卒業させるかです。

この学校では、マークシートを埋めることで進学準備を証明しません。生徒たちは、彼女の遺志を受け継ぎ、自分の物語を語ります。研究論文を書き、科学実験を設計し、正解が一つではない数学の問題を解きます。そして教師や外部専門家の前に立ち、自分の成果を弁護します。思考を説明し、厳しい質問に答え、何度も修正し、再提出を繰り返します。それは「本当に自分のものになった学び」だからです。彼ら一人ひとりの知的自由のための闘いなのです。

この実践は何も新しい発明ではありません。ニューヨーク・パフォーマンス・スタンダーズ・コンソーシアムという38校のネットワークが、30年にわたって築いてきた成果です。生徒たちは、文学・社会・科学・数学の4領域でPBAT(パフォーマンス課題 ーPerformance-Based Assessment Tasks—)を制作します。 パフォーマンス評価です。

文学では分析エッセイ。 社会では授業から生まれた問い(たとえば「なぜ公民権運動はその時代に起きたのか?」)に基づく研究論文。科学では、生徒自身が設計し実施した実験。 数学では、問題解決の過程を言語化した数学レポート。書く量も多いですが、本当に生徒を変えるのは対面発表です。 自分の教師、他校の教員、地域の専門家の前で発表する形式は、まるで大学院の論文審査のようです。評価は長年改良されてきたルーブリックに基づき、年に2回、教師同士が集まって基準をすり合わせます。厳格で、透明性のある公開された制度です。ルーブリックは誰でも閲覧可能です。

学習政策研究所が卒業後の進路を調べたところ、驚くべき結果が出ました。コンソーシアム校の生徒は、より貧困層出身で、共通テストの平均点も低いにもかかわらず、大学1学期の成績が高く、取得単位数も多く、在学継続率も高かったのです。特に黒人男子生徒の大学定着率は、全国平均を大きく上回りました。テストよりも「生徒の提出物」のほうが、進学後の成功を正確に予測していたのです。この生徒たちの提出物こそが、ニューヨーク州の「卒業生の肖像(Portrait of a Graduate)」の基盤となりました。リージェン(高校卒業資格)試験の段階的廃止は、厳しさを捨てたのではありません。ファニー・ルー・ヘイマーのような学校が証明したことを制度が認めたのです。実践から生まれた枠組みでした。

今、欠けているのは、教育者の負担を増やさずにこの仕組みを持ち運び可能で拡張可能にするインフラです。

HS Credでは、生徒自身に最終提出物をデジタル化する追加作業が必要になってきます。自分の学びを「記者」として報道するように、大学や社会に向けて提示するのです。 24ページの論文を10分の動画に変換することは、私たちの世代がパワーポイントで発表したのと同じことです。むしろ編集できる分、動画の方が自由度は高いでしょう。しかし、大学出願時にその提出物はどこへ行くのでしょうか?成績表に取り込まれ、細やかな知的達成は消えてしまいます。HS Credに動画としてアップロードし、大学職員が評価できる形にしない限り、その証拠は失われてしまうのです。HS Credが埋めたいギャップは、生徒自身の手で埋められるべきものです。学術的価値は、生徒の努力から生まれ、それが動画として可視化されます。教師の確認、3人の独立した専門評価者、公開ルーブリックによる評価。4人の合意によってクレジットが認定されます。しかも、その提出物は誰でも見ることができる公開アーカイブとなります。

コンソーシアム校の生徒は、すでにこの力を持っています。PBATをやってきた生徒にとって、10分動画は「新しい学び」ではなく、「新しい形式」なのです。教室は学問のニュースルーム。口頭試問はすでにパフォーマンス。変わるのは観客だけです。

日本の教育者にとって、このモデルは重要でしょう。日本では探究学習が必修化されましたが、高校教育の中でそれほどに評価されていません。「評価すれば腐敗する」という恐れがあるからです。しかし、透明性・公開性・多重評価によって、その腐敗は防げるのです。提出物が公開されるとき、演技は通用しません。考えられるか、考えられないか。説明できるか、できないか。それだけです。ファニー・ルー・ヘイマーが理解していたように、沈黙させられてきた人に必要なのはマイクです。そして大人がそこから退くことです。

私は、テストに引き戻される生徒を見ることにうんざりしています。貧しい学校の優秀な生徒が見落とされることにうんざりしています。能力ではなく従順さを測る制度にうんざりしています。HS Credは、この30年の実践をデジタルのインフラに変え、世界に届けるための仕組みです。10分の動画は、問い・過程・学び・証拠を示すだけ。それだけで十分なのです。ファニー・ルー・ヘイマーは許可を待ちませんでした。声を奪われた者が生きるために、声を取り返したのです。今日の生徒も同じです。拒否されるなら、示せばいい。沈黙を強いられるなら、記録すればいい。

彼らはすでに準備できています。私たちは、その声が世界に届く道をつくるだけです。

2026年2月、HS Credは最初の学生の動画公開を開始します。

立ち上がり、声を上げる生徒たちの声を、ぜひ聞いてください。

ナダブ・ゼマー

HS Cred 創設者/元NYC再建校校長

ビッグ・ピクチャー・ラーニング・リーダーシップ・サミットは、2026年1月26日〜29日にニューヨーク市で開催されます。

#PassionForLearning #AcademicCapital

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025