Dec 8, 2025

The transformation we need doesn't require adult leadership—it requires us to trust students.

———

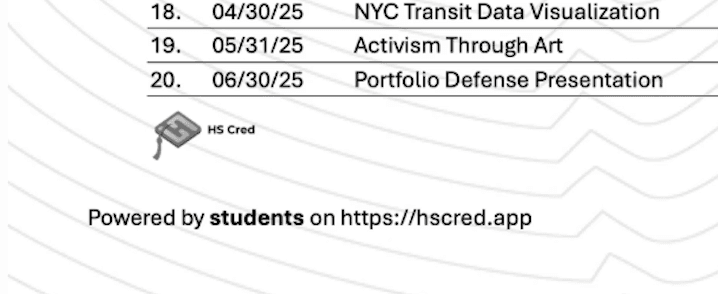

This week I'm presenting at Osaka University in Japan, sharing the HS Cred model with educators exploring how to connect inquiry-based learning (探究学習) with university admissions. The conversation has crystallized something I want to articulate clearly: HS Cred is a student-led initiative. Just look at the bottom of our transcripts.

We don't ask teachers to overhaul their curriculum. We don't ask admissions offices to restructure their review processes. We incentivize students to upgrade their work for publication on our platform—and then we give them the tools to do it.

Most educational innovations fail for the same reason: they add work to already overwhelmed teachers. When I was a physics teacher and robotics coach at George Westinghouse HS, I watched brilliant reform after brilliant reform collapse under the weight of implementation demands. Staff were expected to adopt new curricula, learn new platforms, attend new trainings, grade new assignments—all while managing the actual work of teaching as many as 150 students a day.

When I became a principal, I promised myself and my staff we would find another way. Our success turning around a failing school came partly from this commitment. I raised money to onboard partner organizations who did the reform work in ways that minimized the burden on teachers directly. That's why I've structured HS Cred around a simple principle: if teachers are already using project-based learning, they don't need to change anything. The magic happens on the student side.

Here's what HS Cred asks of an 11th or 12th grader: take the work you're already producing in class and transform it into a polished video presentation of ten minutes or less. Our famous Harlem Renaissance High School (HRHS) Video EXPO events (WNYC coverage, interview, video), held three times per year, gave me the opportunity to work with students on this process hundreds of times. We preceded each showcase with what we called Super Saturday, when volunteers—journalists, community members, parents, political liaisons, friends of teachers—came to help students create videos based on their classwork. Teachers didn't have to stay late or learn video editing. Students got one-on-one support to transform their work into something they could share with the world.

A student writes a research paper for their English teacher? They record themselves reading it aloud, add visuals for key references, and present the result to a real audience of family, peers, and community dignitaries. A science project? They narrate the process, explain their methodology, present their findings. A piece of art? They walk viewers through their creative choices or keep an audio journal they edit down at the end of the term.

The student is responsible for the recording, the editing, the revision, the quality. They're not waiting for permission from their teacher. They're not asking their school to buy new software. They're taking ownership of how their learning gets represented to the world—and in return they get access to elite credentials, validated by university staff.

What we found was that the editing process itself consolidates learning. Listening to a clip over and over about some technical subject, choosing what to leave on the cutting room floor—these activities ensure the student never forgets the academic experience. I regularly run into former students, now in their 30s, who tell me they still remember what they learned at our school because of that process of digitizing and editing their learning for an authentic audience. Our test scores improved in many cases as a result.

The educational research on student agency supports this approach unambiguously. When students take ownership of documenting and presenting their own learning, engagement increases dramatically. And the key to triggering that learning is having an authentic audience who will see their work. A comprehensive body of research shows that student agency—students taking on the role of agents of their own learning while teachers serve as facilitators—produces higher motivation, deeper learning, and better long-term outcomes. The Center for Assessment puts it directly: "Self-directed learning reflects the practical steps of taking ownership of learning, while agency represents the underlying capacity enabling this process." When students control how they demonstrate their knowledge, they develop metacognitive skills that transfer across domains.

This isn't just pedagogical theory. The New York Performance Standards Consortium has demonstrated over twenty-five years that students who engage in performance-based assessment—where they must present and defend their work—achieve higher first-semester college GPAs, earn more credits, and persist at higher rates than peers from traditional testing environments. Notably, these outcomes hold even when Consortium students had lower SAT scores than comparison groups. Authentic student work, produced and presented by students themselves, predicts college success better than standardized tests. What we needed was a way to scale this approach beyond a small network of schools.

When I reach out to educators, I'm always careful to clarify what we're not building. HS Cred is NOT a gradebook—we're not managing assignments or interfacing with your school's information system. HS Cred is NOT curriculum—we don't collect your teaching materials, we don't tell you what to teach, and your intellectual property stays with you. HS Cred is NOT "another platform" that pulls teachers away from teaching—there is very little teachers need to do on our platform until students have finished their final projects. HS Cred is an assessment and verification layer. We don't even require the teacher to complete the final evaluation—we pay three university subject-matter experts to evaluate each and every student submission. The heavy lifting—the recording, editing, revising, submitting—is student work.

As I wrote in the welcome email to CUNY faculty for our upcoming pilot program: "Students are responsible for producing the video that represents their work. HS Cred is a student-led initiative. Your role stays close to what it already is: providing feedback, ensuring the work is original, and upholding academic standards."

Administrators often lecture their teachers about shifting from "Sage on the Stage" to "Guide on the Side." This is a decent framing of the shift from teaching-to-a-test to project-based learning. But here's what they don't address: for a Sage to become a Guide assumes students are motivated to learn and familiar with taking a leadership role in the classroom. For students who have never experienced project-based learning, this is a new concept, and they will resist it at first. That's why journalism is a great place for schools to get started. A newsroom-classroom introduces both project-based learning AND the skills required to record and edit video. With this foundation, a student is ready to convert any classroom learning journey into reportage that can be uploaded to HS Cred for advanced recognition. Administrators must first focus on building a culture of student leadership—something we learned through years of iteration at HRHS. Send the students, not the teachers, to training, and the rest of the transformation happens with plenty of inspiration and not so much effort. In fact, teacher workload can lighten in many instances, allowing them to focus their attention on guiding students rather than filling out paperwork or preparing teacher-centered lesson plans.

The same logic applies on the admissions side: we don't ask admissions offices to change their processes either. When a student earns validated Academic Capital on HS Cred, their work has already been reviewed by the supervising teacher plus three independent subject-matter experts. The multi-rater reliability that makes standardized testing defensible gets applied to authentic student work. Admissions receives a QR code linking to a pre-evaluated portfolio. The quality speaks for itself. This matters because, as David Hawkins of NACAC has noted, the volume of applications at most institutions means there simply isn't the people power to implement something radically different. We're not asking admissions offices to suddenly become video reviewers. We're giving them higher-resolution data about what students can actually do—data that arrives already validated.

I've written before about the distinction between Performance-Based Assessment and Competency-Based Assessment. Both represent alternatives to standardized testing, but they make very different demands on systems. Competency-Based Assessment requires schools to build elaborate tracking infrastructure—determining which competencies each student has mastered, maintaining records of progression, ensuring standardization across classrooms. It's a heavy lift that requires institutional buy-in and coordinated implementation. Performance-Based Assessment asks students to demonstrate what they know by doing something with it. The assessment IS the work product. When that work product is a video—recorded, edited, polished, and submitted by the student—you've captured authentic evidence of learning without building any new infrastructure at all.

This is why HS Cred works within existing project-based classrooms. If a teacher already assigns essays, research papers, presentations, or creative projects, their students can "upgrade" that work for HS Cred submission without the teacher changing anything. The student learns the journalism and digital storytelling skills to transform their assignment into a publishable artifact. The teacher keeps teaching exactly as they were.

What excites me about the work happening in Japan is the recognition that inquiry-based learning needs a pathway to admissions validation. The schools implementing 探究学習 (Tankyū—inquiry-based learning) are producing remarkable student work, though many schools are still not on board with this type of learning. The challenge is that when students graduate, much of that work becomes invisible to admissions offices. HS Cred provides the bridge. A Japanese high school student pursuing inquiry-based research can earn validated Academic Capital from participating universities—without those universities needing to build new evaluation systems, and without Japanese high schools needing to implement new curricula. The path forward is the same in both countries: trust students to lead, provide tools that minimize adult burden, and let the quality of student work create its own momentum.

When HRHS got top grades in the accountability metrics just 18 months after I took over a failing institution, auditors began knocking on our door. The assumption was that we were somehow cheating. I remember one auditor in particular who was sent by the State of New York to see if we were abiding by academic policy in our award of credits. Surely, our increased graduation rate was the result of malfeasance. She arrived unannounced with a computer-generated randomized list of student credits to validate. The proof she requested was straightforward: attendance sheets signed by the teacher, the syllabus for that specific course during that specific term, and the certification of the teacher in charge. In essence, if the "seat time" was achieved, the syllabus aligned with state standards, and the teacher was qualified to teach, the auditor could be confident the student earned the credit.

Because of my remarkable attendance staff, we produced the records without any issue—a feat unto itself, as we must keep all attendance records for seven years, organized so an auditor can pull one out of thin air and we can produce the original immediately. Our guidance team came through with flying colors, producing all the required syllabi, and teacher certification records are managed by the state, so these were readily available. But then I asked the auditor if I might show her the video produced by the student at the end of the class in question. She agreed to watch a few of these videos, and she began to cry. The videos were powerful. She clearly had no doubt the student had done the work—she had just seen it with her own eyes. She left assuring me that we passed the audit and that this was the first time in her career auditing schools that she was so touched, moved, and inspired by the evidence we presented. The quality of student work speaks for itself. Certainly much louder than an attendance sheet and syllabus ever could. In this way HS Cred also makes work easier for administrators too - we handle all the evidence so that you can focus on the needs of your school.

If you're a teacher already using project-based learning, HS Cred asks nothing of you except to keep doing what you're doing. If you're a student ready to take ownership of how your learning gets represented, HS Cred gives you the platform to make your thinking visible to universities. If you're an admissions professional overwhelmed by the volume of applications and the limitations of existing metrics, HS Cred delivers pre-validated evidence of what students can actually do.

We're launching our CUNY STEM Institute pilot in January 2026. We're engaging Japanese schools in this conversation. We're rolling out a fully scalable model that puts students in the driver's seat. The transformation doesn't require anyone to carry a new burden. It requires us to step back and let students lead.

———

Nadav Zeimer is the founder of HS Cred, Inc. and a former NYC turnaround principal. Learn more at hscred.com.

#PassionForLearning #AcademicCapital

This week I'm presenting at Osaka University in Japan, sharing the HS Cred model with educators exploring how to connect inquiry-based learning (探究学習) with university admissions. The conversation has crystallized something I want to articulate clearly: HS Cred is a student-led initiative. Just look at the bottom of our transcripts.

We don't ask teachers to overhaul their curriculum. We don't ask admissions offices to restructure their review processes. We incentivize students to upgrade their work for publication on our platform—and then we give them the tools to do it.

Most educational innovations fail for the same reason: they add work to already overwhelmed teachers. When I was a physics teacher and robotics coach at George Westinghouse HS, I watched brilliant reform after brilliant reform collapse under the weight of implementation demands. Staff were expected to adopt new curricula, learn new platforms, attend new trainings, grade new assignments—all while managing the actual work of teaching as many as 150 students a day.

When I became a principal, I promised myself and my staff we would find another way. Our success turning around a failing school came partly from this commitment. I raised money to onboard partner organizations who did the reform work in ways that minimized the burden on teachers directly. That's why I've structured HS Cred around a simple principle: if teachers are already using project-based learning, they don't need to change anything. The magic happens on the student side.

Here's what HS Cred asks of an 11th or 12th grader: take the work you're already producing in class and transform it into a polished video presentation of ten minutes or less. Our famous Harlem Renaissance High School (HRHS) Video EXPO events (WNYC coverage, interview, video), held three times per year, gave me the opportunity to work with students on this process hundreds of times. We preceded each showcase with what we called Super Saturday, when volunteers—journalists, community members, parents, political liaisons, friends of teachers—came to help students create videos based on their classwork. Teachers didn't have to stay late or learn video editing. Students got one-on-one support to transform their work into something they could share with the world.

A student writes a research paper for their English teacher? They record themselves reading it aloud, add visuals for key references, and present the result to a real audience of family, peers, and community dignitaries. A science project? They narrate the process, explain their methodology, present their findings. A piece of art? They walk viewers through their creative choices or keep an audio journal they edit down at the end of the term.

The student is responsible for the recording, the editing, the revision, the quality. They're not waiting for permission from their teacher. They're not asking their school to buy new software. They're taking ownership of how their learning gets represented to the world—and in return they get access to elite credentials, validated by university staff.

What we found was that the editing process itself consolidates learning. Listening to a clip over and over about some technical subject, choosing what to leave on the cutting room floor—these activities ensure the student never forgets the academic experience. I regularly run into former students, now in their 30s, who tell me they still remember what they learned at our school because of that process of digitizing and editing their learning for an authentic audience. Our test scores improved in many cases as a result.

The educational research on student agency supports this approach unambiguously. When students take ownership of documenting and presenting their own learning, engagement increases dramatically. And the key to triggering student learning is having an authentic audience who will see their work.

A comprehensive body of research shows that student agency—students taking on the role of agents of their own learning while teachers serve as facilitators—produces higher motivation, deeper learning, and better long-term outcomes. The Center for Assessment puts it directly: "Self-directed learning reflects the practical steps of taking ownership of learning, while agency represents the underlying capacity enabling this process." When students control how they demonstrate their knowledge, they develop metacognitive skills that transfer across domains.

This isn't just pedagogical theory. The New York Performance Standards Consortium has demonstrated over twenty-five years that students who engage in performance-based assessment—where they must present and defend their work—achieve higher first-semester college GPAs, earn more credits, and persist at higher rates than peers from traditional testing environments. Notably, these outcomes hold even when Consortium students had lower SAT scores than comparison groups. Authentic student work, produced and presented by students themselves, predicts college success better than standardized tests. What we needed was a way to scale this approach beyond a small network of schools.

When I reach out to educators, I'm always careful to clarify what we're not building. HS Cred is NOT a gradebook—we're not managing assignments or interfacing with your school's information system. HS Cred is NOT curriculum—we don't collect your teaching materials, we don't tell you what to teach, and your intellectual property stays with you. HS Cred is NOT "another platform" that pulls teachers away from teaching—there is very little teachers need to do on our platform until students have finished their final projects. HS Cred is an assessment and verification layer. We don’t even require the teacher to complete the final evaluate - we pay three university subject-matter experts to evaluate each and every student submission. The heavy lifting—the recording, editing, revising, submitting—is student work.

As I wrote in the welcome email to CUNY faculty for our upcoming pilot program: "Students are responsible for producing the video that represents their work. HS Cred is a student-led initiative. Your role stays close to what it already is: providing feedback, ensuring the work is original, and upholding academic standards."

Administrators often lecture their teachers about shifting from "Sage on the Stage" to "Guide on the Side." This is a decent framing of the shift from teaching-to-a-test to project-based learning. But here's what they don't address: for a Sage to become a Guide assumes students are motivated to learn and familiar with taking a leadership role in the classroom. For students who have never experienced project-based learning, this is a new concept, and they will resist it at first. That's why journalism is a great place for schools to get started. A newsroom-classroom introduces both project-based learning AND the skills required to record and edit video. With this foundation, a student is ready to convert any classroom learning journey into reportage that can be uploaded to HS Cred for advanced recognition. Administrators must first focus on building a culture of student leadership—something we learned through years of iteration at HRHS. Send the students, not the teachers, to training and the rest of the transformation happens with plenty of inspiration and not so much effort. In fact, teacher workload can lighten in many instances, allowing them to focus their attention on guiding students rather than filling out paperwork or preparing teacher-centered lesson plans.

The same logic applies on the admissions side: we don't ask admissions offices to change their processes either. When a student earns validated Academic Capital on HS Cred, their work has already been reviewed by the supervising teacher plus three independent subject-matter experts. The multi-rater reliability that makes standardized testing defensible gets applied to authentic student work. Admissions receives a QR code linking to a pre-evaluated portfolio. The quality speaks for itself. This matters because, as David Hawkins of NACAC has noted, the volume of applications at most institutions means there simply isn't the people power to implement something radically different. We're not asking admissions offices to suddenly become video reviewers. We're giving them higher-resolution data about what students can actually do—data that arrives already validated.

I've written before about the distinction between Performance-Based Assessment and Competency-Based Assessment. Both represent alternatives to standardized testing, but they make very different demands on systems. Competency-Based Assessment requires schools to build elaborate tracking infrastructure—determining which competencies each student has mastered, maintaining records of progression, ensuring standardization across classrooms. It's a heavy lift that requires institutional buy-in and coordinated implementation. Performance-Based Assessment asks students to demonstrate what they know by doing something with it. The assessment IS the work product. When that work product is a video—recorded, edited, polished and submitted by the student—you've captured authentic evidence of learning without building any new infrastructure at all.

This is why HS Cred works within existing project-based classrooms. If a teacher already assigns essays, research papers, presentations, or creative projects, their students can "upgrade" that work for HS Cred submission without the teacher changing anything. The student learns the journalism and digital storytelling skills to transform their assignment into a publishable artifact. The teacher keeps teaching exactly as they were.

What excites me about the work happening in Japan is the recognition that inquiry-based learning needs a pathway to admissions validation. The schools implementing 探究学習 (Tankyū—inquiry-based learning) are producing remarkable student work (given, many schools are still not on board with this type of learning). The challenge is that when students graduate, much of that work becomes invisible to admissions offices. HS Cred provides the bridge. A Japanese high school student pursuing inquiry-based research can earn validated Academic Capital from participating universities—without those universities needing to build new evaluation systems, and without Japanese high schools needing to implement new curricula. The path forward is the same in both countries: trust students to lead, provide tools that minimize adult burden, and let the quality of student work create its own momentum.

When HRHS got top grades in the accountability metrics just 18 months after I took over a failing institution, auditors began knocking on our door. The assumption was that we were somehow cheating to achieve such metrics. I remember one auditor in particular who was sent by the State of New York to see if we were abiding by academic policy in our award of credits. Surely, our increased graduation rate was the result of malfeasance. The auditor arrived unannounced and had a computer-generated randomized list of student credits they had to validate for the audit. In essence they wanted proof that the selected credits were earned and not given to the student without the required academic achievement. The proof they requested was (1) attendance sheets signed by the teacher showing how many times the student attended class (2) they syllabus for that specific course during that specific term (3) the certification of the teacher in charge. In essence, if the “seat time” was achieved and the syllabus was aligned with state standards and the teacher was qualified to each the auditor could be confident that the student earned the credit in question. Because of my remarkable attendance staff we came up with the attendance records without any issue - that is a feat unto itself as we must keep all attendance records for seven years and we must keep them organized so that an auditor can pull one out of thin air and we must be able to produce the original form immediately. Our guidance team also came through with shining colors, producing all the required syllabi and teacher certification records are managed by the state so these were readily available. But then I would ask the auditor if I might show her the video produced by the student at the end of the class in question. The auditor agreed to watch a number of these videos and she began to cry. The videos were really powerful. She clearly had no doubt that the student had done the work in question - she just saw it with her own eyes. The quality fo student work speaks for itself. Certainly much louder than an attendance sheet and syllabus can ever do.

If you're a teacher already using project-based learning, HS Cred asks nothing of you except to keep doing what you're doing. If you're a student ready to take ownership of how your learning gets represented, HS Cred gives you the platform to make your thinking visible to universities. If you're an admissions professional overwhelmed by the volume of applications and the limitations of existing metrics, HS Cred delivers pre-validated evidence of what students can actually do.

We're launching our CUNY STEM Institute pilot in January 2026. We're engaging Japanese schools in this conversation. We're rolling out a fully scalable model that puts students in the driver's seat. The transformation doesn't require anyone to carry a new burden. It requires us to step back and let students lead.

———

Nadav Zeimer is the founder of HS Cred, Inc. and a former NYC turnaround principal. Learn more at hscred.com.

#PassionForLearning #AcademicCapital

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

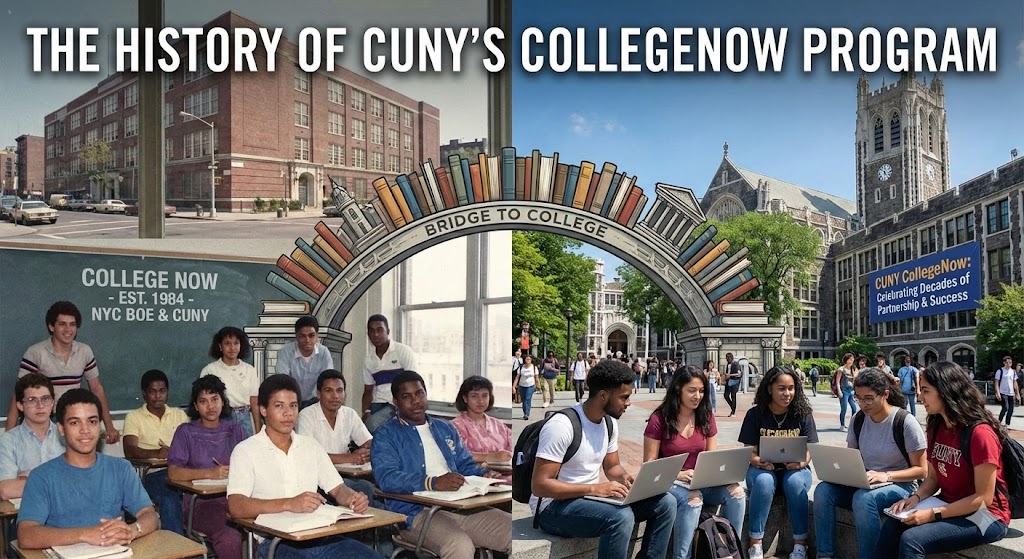

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025