Jan 31, 2026

by Nadav Zeimer

I spent nearly an entire workweek in Harlem last week at Big Picture Learning's Leadership Summit—"The City as the Classroom"—and I came home with a relationship to leadership I wasn't expecting. It arrived Tuesday night during a session called "Shameka and Elliot After Dark," when the conversation turned to perfectionism. This is an organization grown in the practice of leadership, so it is no wonder they might lead me to a deeper understanding of it.

Shameka asked us to consider perfectionism. It is fear wearing a suit. It's the terror of being seen as less than flawless—of making a mistake, of being caught not knowing, of being exposed as someone who doesn't deserve the role. Furthermore, the experience of perfectionism embodied is overwhelm. That was my experience of it. I am not overwhelmed as a function of workload. Not even complexity. Perfectionism is the context that yields overwhelm. I need overwhelm as an excuse for some specific thing that is not getting done.

Think about it. I can have a project that is about to lead to a massive promotion—lots of extra work. But it is inspiring, exciting rather than overwhelming. I'm meeting a new community of top brass and I'm feeling like a million bucks, teams are showing up to help me do more than I thought possible. Although overwhelm is equally available as an excuse, I'm not looking for excuses. The emergent narrative becomes one of an exciting time.

The perfectionist cannot take imperfect action. That's the conundrum. In a world that is very much organic—and hence has some disregard for synthetic, human-imagined perfection—all action is imperfect. Third and fourth order waves ripple out beyond anyone's control, in the glory of consequences. So the perfectionist hesitates. Waits for conditions to be right. Procrastinates. Prepares endlessly. Rehearses. Researches. Edits. Stalls. I've lived there more often than I care to admit. And while all that stalling is happening, the perfectionist is overwhelmed. Spinning—performing busyness, projecting competence, looking extremely productive while avoiding the one vulnerable action that might actually move something forward.

That avoidance creates the suffering I call overwhelm. I expect myself to be a perfect robot in a perfectly designed world, and when things don't go that way, I'm overwhelmed, claiming it is because I have too much to do. But the real source is what I'm not doing. All the work I am doing that is not that one thing I know I am avoiding. What I'm afraid to do imperfectly. What I care the most about!

Only machines can be perfect in this way. A machine executes instructions without hesitation, without doubt, without the need for rest or reflection. It does not wonder whether it deserves its role. It does not fear being seen as less than flawless because it has no self to protect. When I demand perfection of myself—when I try to execute without error, to produce without pause, to perform without vulnerability, to do deep work and never need to take a nap at my desk—I am asking myself to be something I am not. I am treating myself as a machine. And overwhelm is what humans experience when they try to pretend we are robots. The body rebels. The mind spins. I feel the weight of a demand that was never designed for creatures who bleed and doubt and need sleep and crave depth of experience. Entire societies have tried to train this out of their citizens, to create cultures where humans function as interchangeable parts. The results are always the same: compliance in public, suffering in private, and eventually a generation that refuses to keep pretending.

It's because I care so much that I tell myself to be so perfect. So what am I caring so much about? Ultimately it is a position, a job, a role, a title. Something that can be taken away from me. If overwhelm has nothing to do with what I am doing and everything to do with what I am avoiding, the antidote must be to get into action! But it's not so simple. Clearly, if I take even incomplete action, even imperfect action, the overwhelm disappears. No more spinning in circles. But empty action leads to more overwhelm. It's the stuckness that creates the suffering, not the workload. The paralysis. The pretending to be busy while avoiding the thing that actually matters. Overwhelm is what happens when perfectionism has convinced me that moving forward imperfectly is more dangerous than staying still. But instead of being still in a state of rest to build strength and perspective, I pretend to be so busy, robbing myself of an opportunity to heal and recharge even though the amount of meaningful forward motion is the same as if I were actually taking a nap at my desk and snoring loudly.

So let me now be clear. When I feel overwhelmed, when I feel tight and urgent and brittle, what I'm experiencing is not leadership. It's the fear of losing a position. The title. The recognition. The sense that I matter because of where I sit on an org chart. That kind of fear produces perfectionism, and perfectionism produces paralysis. And paralysis produces a very specific kind of culture. A culture of control. A culture where people are quiet and careful and political. A culture that cannot, by definition, create anything new because it can never do the deep careful work of healing the past to make room for something new in the future.

I walked out of that session at the BPL conference last Tuesday and wrote an email to my colleagues before I went to bed. The next morning we continued the conversation at the Museum of the City of New York, and over lunch, and through the final debrief of the conference. By the time I got back to my office, I had a new way of seeing something I'd been circling for years.

There are two worlds that get called "leadership," and confusing them is where a lot of talented people lose their footing. The first is positional leadership. It's title-based. It flows from whoever holds the position at the top of an organizational structure. I chase it because it comes with recognition, salary, and the subtle social promise of "I matter here." But positional leadership is really about maintaining what already exists. It is about leading something that already has a hierarchy with titles and clearly defined roles. I am keeping the machine running, increasing quality and effectiveness of inputs and outputs. This is necessary work—schools need management, systems need continuity. Machines are very useful! But it is not the kind of leadership that creates a new future among a bunch of messy human beings.

The second type of leadership is something I'll call organic leadership, for lack of a better term. If only because the analogy to a gardener is so apt. It has nothing to do with positions of authority and everything to do with network effects and playing in the dirt. It cannot come from the top down because no hierarchy exists for it to flow through. Think of mycelia functioning underground, connecting a forest in ways no single tree controls. This kind of distributed leadership is about healing rather than fixing. It is about who I am being more than what I am doing. It allows results to emerge rather than implementing them by mandate or command. It is about listening for what wants to happen rather than dictating what must get done.

I know the difference between these two because I have lived both, often in the same week. When I was a high school principal, we would have days when the superintendent came to visit. Evaluation days. My superintendent was often a friend of mine, someone who had previously been a peer principal. Neither of us particularly enjoyed these experiences. But we were playing the robot cogs in the administrative wheels that power the machine and we couldn't afford to break anything. We were, after all, being paid taxpayer dollars and we must be top performers lest we be wasteful or inefficient. Efficiency is a great measure for a machine, but not for a human leader.

Those were the days that determined whether I kept my job, whether the school kept its rating, whether everything I had built would continue or be dismantled by someone who spent four hours in the building and thought they understood us. On those days, I was never a leader. I was a manager. I was terrified. Terrified of being evaluated. Terrified of being called out as a fraud who didn't deserve the role. Terrified of losing the position I had worked so hard to earn. I was full-on positional. And that's the stupidest form of myself as a principal. An empty role robot without my human instincts intact. That fear killed any possibility of authentic leadership being present from me on those days. I was performing competence instead of generating it. I was managing impressions instead of creating conditions. I was, in the deepest sense, stuck—even while running around looking extremely busy. I was trying to be an efficient machine.

Here's the strange part: the school did well on those visits anyway. Not because of me. Because I had led before that day, and the culture I had helped create didn't depend on me being present. I’m only that important in a hierarchy, but in organic leadership terms, I’m just one node that can afford to fail. That's the resilience of organic leadership—it exists because of favorable conditions created by every person in the community, not just one person at the top. Students stepped up. Teachers who weren't frozen by the same terror I felt carried the weight. The community functioned because leadership had already taken root, and that leadership didn't require me to be in the room performing my role. Thankfully I had planted the seeds and watered the soil long before that dreadful visit.

This experience taught me something I've never heard anyone say out loud, so I'll say it here: maybe the best way for superintendents to evaluate a school is to send the principal home that day. Help them revive and recharge. They are useless in the building that day, anyway! Spend city dollars to send them to a spa or yoga or something super rejuvenating. But do the visit without them! If the school is organically strong, the community will lead in the principal's absence. If it's not, the superintendent will get honest input without the dog-and-pony show that fear always produces. The principal's presence during an evaluation creates exactly the conditions that make organic leadership impossible.

That experience of being the stupidest version of myself was familiar to me. It's the same version of myself that would settle into my socks when, in high school, the proctor pedagogue called out "THE TEST BEGINS NOW." I would immediately get so nervous that I would have a mini nervous breakdown, and that is what I call the stupidest version of myself. Later in life I learned how to study and I could walk into a test with confidence and ease and retain my intellectual capacity. But that wasn't until my final years of university. As a principal I would hear "THE EVALUATION BEGINS NOW" and I would turn into that same daft teenager in meltdown.

Carlos Moreno, the co-executive director of Big Picture Learning, wrote a book called "Finding Your Leadership Soul" that sits at the heart of this distinction between positional and organic leadership. His framework rests on three principles: lead with love, lead with care, lead with vulnerability. These are not soft ideas. They are the opposite of what positional leadership typically demands. These are hard work, and I'm not talking about complicated paperwork. This is deep work with much healing as a prerequisite. Positional leadership says: be certain, be in control, be invulnerable. Moreno's framework says: be present, be connected, be willing to not know. Elliot Washor, co-founder of Big Picture Learning, describes the book as requiring you to "think with your body but feel with your mind." That inversion is the whole point. I have been trained to lead from the neck up, from the org chart down, from the position outward. Moreno is pointing toward something that moves in the opposite direction—leadership that emerges from presence rather than position, from connection rather than control.

But what does it actually mean to lead without force? I'm a physicist by training, so when I hear words like "power" and "force," my mind goes to technical definitions. In human systems, I've noticed that we confuse the two. Force says: do it because I said so, do it because I can reward you or punish you, do it because the metrics demand it. Force can produce motion, but it rarely produces ownership. It rarely produces learning. It rarely produces the kind of emergence that creates something genuinely new. Moreno's leadership requires a different kind of power altogether—one that doesn't push people into motion but creates conditions where motion arises organically.

To understand the difference between being paralyzed and being propelled as a leader we come to one of my favorite areas of brain research that I explore in the second edition of my book "Education in the Digital Age," being released later this year. This research shows that fear and excitement are physiologically identical. They trigger the same brain functions, release the same chemicals, produce the same physical reactions in the body: heart racing, stomach churning, knees weakening. The difference is narrative. If I believe the impending unknown will end well, I experience excitement. If I believe it will end badly, I experience fear. The story I tell myself about the future determines whether I am effective or not, like a self-fulfilling prophecy. Force backfires because it generates fear, and fear narrows cognition, and narrowed cognition produces exactly the paralysis that force was supposed to overcome. You get the stupidest version of everyone and we spin the narrative of failure.

This is why educators matter so much: they help craft that narrative for each student in their care. This is why leadership in education is different from leadership in other sectors. Educators invent futures. They see what is possible for a young person before that person sees it for themselves. Their success has less to do with scripted actions than with a way of being that students experience with all their senses. A teacher's belief that things will work out for a student can literally change whether that student experiences school as threatening or exciting. The same is true for leaders. A principal's belief that the community can handle a challenge—that the superintendent's visit will go fine even without a perfectly orchestrated performance—changes what becomes possible. The narrative the leader holds shapes the culture the community inhabits and determines whether teachers will lead their students into a future not based on the past and whether students will similarly lead the community through their inquiry and discovery of what is possible.

And this is where leadership and learning become the same thing. In the book, I share other research showing how the human brain is designed to find joy in the act of learning. That joy is what makes learning intrinsically motivating—it's why toddlers don't need to be forced to learn language or walking. They are driven by something internal. That same drive exists in teenagers and adults, but industrial schooling has spent a century trying to suppress it in favor of mechanical compliance. When I talk about "student engagement," I'm really talking about whether the system has managed to extinguish that natural drive to create something original, something flawed and organic—that early experience of leadership.

What I realized at the conference is that the same thing is true of adult leadership. The human capacity to lead—to take responsibility, to form a team, to move something from here to there, to cause change in the world around us—is not rare. It is not the province of the few who hold positions. It is as natural as learning itself. In fact, it is same thing. To learn is to change. To lead is to cause movement. If I define management as a person who is responsible for a team of people, then leadership is also a person who causes other people to manage a team of people. A learner who takes ownership of their education is learning to lead. A community of learners who take ownership of their community is a community of leaders. A leader of leaders is the one who establishes organic conditions for leadership to arise in their fellow organic matter.

This reframes everything about what schools are supposed to do. If leadership is learning, then the purpose of a school is not to produce compliant workers who follow instructions. The purpose is to develop leaders—people who can take responsibility for problems that don't have predetermined answers, who can navigate complexity without being paralyzed by it, who can cause the leadership of others rather than hoarding power for themselves. This is what causes network effects—exponential spread. Nothing is exponential in real world conditions like organic life! No matter how much they may try, synthetics can rarely compete.

A principal leader causes teachers to be classroom leaders who cause student leaders. They are all sharing the same conditions that sprout leadership. Each leader causes the leadership of others and so on. It is bottom up, so the principal can be just one human being leading others, creating teams and teamwork in a network of others doing the same. More or less.

The facilitators of the Big Picture conference chose to close our final breakout session with the work of Tricia Hersey and The Nap Ministry. This was my first interaction, in the form of a beautifully designed set of laminated cards. Fun and yet pretty revolutionary. She calls her book a manifesto. Hersey's core idea is that rest is resistance—not rest as luxury or self-care, but rest as a disruption of the systems that treat human beings as machines for production. She writes about how grind culture has convinced us that our worth is tied to our productivity, that slowing down is failure, that exhaustion is proof of commitment. And she argues that refusing to be exhausted is itself an act of leadership. It creates space for imagination. It makes room for emergence. It resists the logic that says the only way to matter is to be constantly, visibly, productively busy.

This resonated deeply with the perfectionism conversation from earlier in the week. Perfectionism keeps me spinning. It keeps me performing busyness while avoiding the vulnerable action that might actually change something. It keeps me in a state that looks like motion but is actually paralysis. Hersey's invitation to rest is not an invitation to do nothing. It's an invitation to stop performing and start being present. To trade the appearance of leadership for the conditions that allow leadership to emerge, organically, the way a gardener leads her garden. The way Carlos Moreno wrote about leadership.

And this is where the insight stops being individual and becomes structural. Because the logic of grind culture doesn't just burn out individual leaders—it shapes entire societies. My wife grew up in Japan, and she describes how the education system there trains humans to be robots. Not metaphorically. Systematically. This from the same society that gave us wabi-sabi, which bows in reverence to the organic over the synthetic—the cracked bowl more beautiful for its imperfection, the moss-covered stone more precious than polished marble. And yet.

From the earliest grades, children learn that conformity is safety and deviation is danger. School rules govern everything from the length of socks to the angle at which students must raise their hands to speak. Students with naturally brown hair have been forced to dye it black because the assumption of uniformity leaves no room for natural variation. Immigrants spend generations in Japan without ever becoming citizens. The highly homogenous classroom—same age, same uniform, same expectations—creates what Japanese educators call a stifling atmosphere where students learn to read the unspoken expectations of their peers and behave accordingly rather than think for themselves.

This is what it looks like when the machine metaphor becomes a national curriculum. The Japanese word gaman captures the expectation: endure without complaint, persevere without expressing distress, sacrifice individual needs for group harmony. It is taught from childhood as a virtue, and there is genuine wisdom in it—resilience matters, and the ability to persist through difficulty is valuable. But gaman has a shadow side. When children learn that the proper response to injustice or exhaustion is silent endurance, they lose access to the very capacities that authentic leadership requires: the ability to name what is wrong, to advocate for change, to say "this is not working" before the body breaks down.

Japan has a word for what happens when gaman meets grind culture: karoshi. Death from overwork. The phenomenon has claimed thousands of lives—heart attacks, strokes, suicides—and spawned an entire body of labor law attempting to address what was once considered simply the price of dedication. A primary legal fight for educators in Japan has to do with overwork.

In 2015, a twenty-four-year-old woman named Matsuri Takahashi took her own life after logging over a hundred hours of overtime in a single month. Just before her death, she posted online: "I'm at work twenty hours a day or so, and I no longer know what I'm living for." Her case became a national inflection point, forcing legislative change and sparking a conversation that continues today.

It is a conversation about perfectionism. The kind that paralyzes individual leaders is the same logic that, scaled to a society, produces karoshi. When I treat humans as machines—when I demand flawless execution without rest, compliance without complaint, productivity without pause—I create cultures where people work themselves to death or disappear into silence. Japanese schools that enforce identical haircuts and regulate the number of pencils in a pencil box are not preparing students for a complex future. They are preparing workers for an industrial past that no longer exists. The conformity that once rebuilt a nation after war has become a weight that younger generations are beginning to refuse to carry.

And they are refusing. This is the part of the story that gives me hope. Japan passed a national call for inquiry-based learning years before New York State did so with Portrait of a Graduate, and New York is considered among the leaders. Surveys show that nearly half of young Japanese workers are now "quiet quitting"—fulfilling their duties but consciously rejecting the culture of overwork. Average annual working hours have fallen by double digits since 2000, bringing Japan closer to European norms. Young people are prioritizing personal time, mental health, and meaningful work over the lifetime employment their parents pursued. A professor at Hokkaido Bunkyo University put it simply: "Young people are deciding that they do not want to sacrifice themselves for a company. And I think that is quite wise."

This generational shift is organic leadership emerging from the ground up. No one mandated it. No position of authority decreed it. Young Japanese workers looked at the system their parents accepted and said: this is not how I want to live. They are choosing rest as resistance, even in a culture where resistance has historically been suspect. They are proving that the human drive toward authentic life cannot be extinguished permanently, even by a century of industrial conditioning. The machine model of human productivity is breaking down not because governments passed laws—though some have—but because people are reclaiming their humanity one boundary at a time.

What does this mean for educators building the post-test era? It means the work I am doing is not just American. It is not just about replacing standardized exams with performance-based assessment. It is about reclaiming what education is for. Industrial schooling was designed to produce factory workers—compliant, punctual, able to follow instructions. That model made sense when the economy needed humans who could function as interchangeable parts. But the digital economy values exactly what factories suppressed: organic humanity. Creativity, initiative, the ability to navigate ambiguity, the courage to ask questions no one has asked before. These are the capacities that emerge when I stop treating students as machines and start treating them as leaders of their own learning.

Japan's inquiry-based learning movement—what they call Tankyu—is pushing in exactly this direction. Students investigate real problems, conduct original research, and present their findings to panels. The methodology produces exactly the deep thinking that colleges claim to value and that employers actually need. But the work doesn't count for university admissions, and the fear is that connecting it to high stakes will corrupt it. Sound familiar? The same tension exists everywhere that authentic assessment tries to coexist with a system built on standardized metrics. The question is whether we can build infrastructure that makes genuine thinking visible without reducing it to another form of test prep.

Standardized testing culture was built on force. It centralized authority. It rewarded compliance. It treated learning like a manufacturing output and students like products to be quality-controlled. The entire architecture assumed that answers can come from the top down on an answer key. That student thinking can be scripted by those writing standards. That architecture requires positional leadership to function. It requires people at the top who issue mandates and people below who execute them. It requires everyone to be afraid of the metrics.

Performance-based assessment assumes the opposite. Quality is visible in authentic work. Judgment is strengthened through multiple perspectives and calibration. Learning improves through feedback loops, iteration, and public criteria. That model is inherently decentralized. It's closer to peer review than corporate or government central control. It requires what Moreno calls vulnerability—the willingness to be seen, to be wrong, to revise. It requires what I'm now thinking of as authentic rest—the spaciousness to listen, to notice, to respond rather than react.

This is why the shift beyond standardized testing is also a shift in our theory of leadership. Organic leadership spreads through relationships. It scales through recursion: I cause leadership in someone else, and they cause it in someone else, and soon there is a culture where initiative isn't rare—it's normal. The phrase that keeps echoing in my mind: leadership is when one group member modifies the motivation or competencies of others. Not "being in charge." Shifting what becomes possible around you. That's the whole game.

And if leadership is learning, then this recursive spreading of leadership is exactly what education is supposed to produce. Each learner becomes a leader who causes learning in others. Each student who takes ownership of their inquiry becomes someone who can cause ownership in peers. The classroom stops being a place where knowledge flows one direction—from teacher to student, from answer key to test-taker—and becomes a network where everyone is simultaneously learning and leading, causing change in themselves and in each other. That is what a decentralized learning community looks like. That is what the post-test era makes possible.

In my book, I describe what happens when students are given ownership of their education: they step up. A friend of mine covered an AP physics class as a long-term substitute despite having no physics background whatsoever. She managed behavioral expectations and then got out of the way. The students taught each other from books, did practice problems together, and every single one of them passed what is known as among the hardest of all high school exams. She jokes that she could have been replaced by a potted plant. But what she actually did was create the conditions for student leadership to emerge. She didn't teach physics. She caused the students to teach each other.

That story only worked because those students were already motivated. The deeper question is: how do I create that motivation in every school, not just elite ones? The answer, I believe, is to stop trying to motivate students and start creating conditions where their natural drive to learn—and therefore to lead—isn't suppressed. Industrial schooling kills that drive by treating students as recipients rather than agents, as followers rather than influencers, as empty vessels to be filled rather than fires to be lit. Performance-based assessment inverts that model. It asks students to produce, to create, to demonstrate what they can do. It treats them as leaders of their own project. And when students lead their own learning, they become capable of causing learning in others. The teacher's work deepens and their impact spreads.

I want to close with an old cliché: with great power comes great responsibility. But the inverted form is where I want to bring your focus: with great responsibility comes great power. Those who take responsibility for some part of the world around them—who decide that they are the ones who must move something from here to there—they are leading. The word itself contains the insight: response-able. Able to respond. Free to participate. Willing to make things around you workable. This is often bad news for people who prefer to have someone in a position of power to point at and blame. It turns out there is nothing stopping any of us from taking on this kind of leadership. The barrier is not permission. The barrier is fear.

Here's the practical reframe I'm taking from the conference into next week. When I feel overwhelmed, I'm going to ask myself two questions. First: what am I avoiding? What action am I not taking? What conversation am I not having? Where am I unable to respond? What decision am I not making? Overwhelm is almost always a symptom of avoidance, and the cure is almost always movement. Not perfect movement. Just movement. Second: what am I afraid of losing? Reputation? Control? Approval? The identity of "the competent one"? The comfort of being needed? Sometimes the honest answer will be that I'm afraid of losing positional standing. And once I can say that plainly, I can stop pretending my stress is noble. I can stop performing leadership and start practicing it or recognizing it in those around me.

The future of education cannot be commanded into existence. The credibility infrastructure required—transparent, calibrated, networked, resilient against corruption—will only work if it is built by people who have stopped trying to control outcomes and started creating conditions. Conditions for students to demonstrate what they can actually do. Conditions for professors to evaluate work based on evidence rather than pedigree. Conditions for schools to shift from compliance cultures to learning cultures—which is to say, leadership cultures. Schools that develop portfolios rather than take tests.

That work requires leaders who measure their success by how much leadership they cause in others. Leaders who know that the community should be able to function—maybe even function better—when they're not in the room. On my best days as a principal, I wasn't the one leading. I was the one who had created the conditions for everyone else to lead. I may have even been sleeping at my desk. On my worst days, I was the one performing leadership so hard that I crowded out everyone else's capacity to step up. The post-test era needs the first kind. The second kind is what got us here.

Nadav Zeimer is the founder of HS Cred, Inc. and a former NYC turnaround principal. The Big Picture Learning Leadership Summit took place January 26–29, 2026 in New York City. For Japanese readers interested in connecting inquiry-based work to global audiences, visit hscredjp.org.

#PassionForLearning #AcademicCapital #BPLLeadershipSummit #探究学習

Professors, Not Permissions

Feb 1, 2026

City as Teacher, World as Audience

Jan 26, 2026

Sick and Tired of Being Tested

Jan 19, 2026

Inquiry Without Corruption

Jan 12, 2026

Powered by Students: Why HS Cred Asks Not of Teachers nor Admissions Offices

Dec 8, 2025

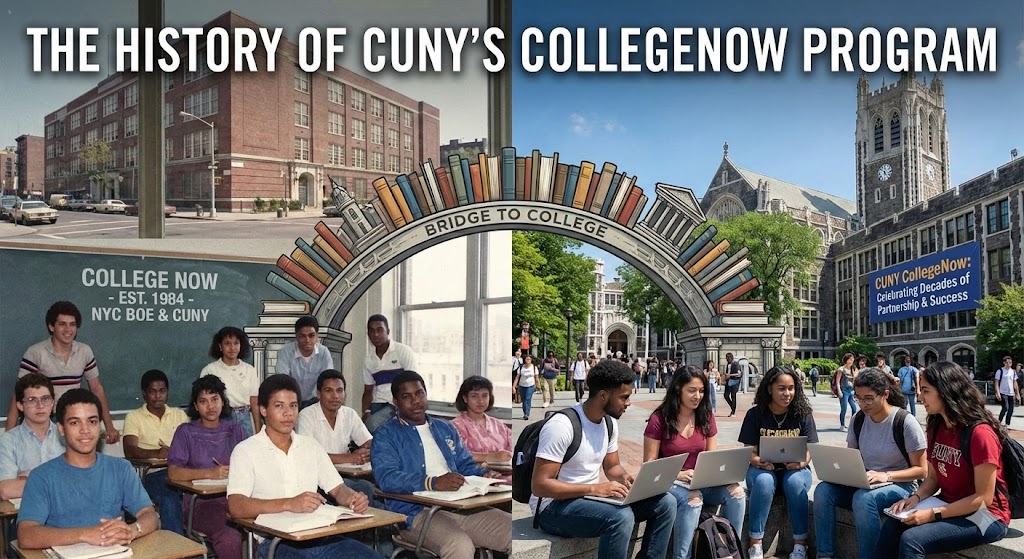

How 'College Now' Paved the Way for Today's Assessment Revolution

Dec 2, 2025

NYC's Path Beyond Standardized Testing May Surprise You

Nov 24, 2025

PBA vs. CBA: The Right Way to Transform Assessment in New York

Nov 18, 2025

Election Day 2025: Shaping NYC's Educational Landscape

Nov 4, 2025

Financial Jiu Jitsu

Oct 28, 2025

Two Julies in Albany

Oct 20, 2025

Bridging the Gap: What Japan’s Independent Study Model Teaches Us About College-Ready Inquiry

Oct 9, 2025

Standardized Tests Are Sunsetting: What's Next for College Admissions?

Sep 29, 2025

Academic Capital: The New Gold Standard of Student Achievement

Sep 22, 2025

An Education System That Makes the Old One Obsolete

Aug 25, 2025